Chapter 8: The Nationalist War Effort

The balance of forces in the first phase

"the Popular Front dominated most of the larger cities, all the industrial areas, most of Spains financial resources, most of the existing stock of military materiel, and the bulk of the Navy and Air Force. Moreover, the political militias formed by the revolutionary organizations at first considerably outnumbered the military auxiliaries of the Nationalists.

...The Army was not at full strength when the conflict began, because of incomplete recruitment and even more because at least one- third of the nominal 180,000 troops under arms were on summer leave.

...round 55,000 for each side, though the actual available manpower may well have been less than that in both cases. Moreover, the Republicans retained the services of at least 60 percent of the 5,300 Air Force personnel, nearly two-thirds of the 20,000 Navy personnel (though minus many of their officers, slaughtered by crewmen in the first days), and slightly more than half of the armed police. Thus the Republican forces began with a slight numerical advantage in organized personnel, in addition to general air and naval control.

This nominal advantage was, however, soon eroded by the effects of the revolution, which was determined to destroy the remains of the regular armed forces and replace them with political militia. Thus during the first weeks of the Civil War those military units remaining in the Republican zone were progressively dissolved by the revolution until few remained. Of the slightly more than 15,000 officers in the Spanish Army in 1936, at least half found themselves in the Republican zone. Only a small minority of these rebelled during the weekend of July 18, but approximately 3,000 were purged during the next few weeks. Some 1,500 were sooner or later executed and the remainder imprisoned. Another thousand or so managed either to flee the Republican zone or find hiding within it, while approximately 3,500 served the Republican forces during the Civil War.

...Even those Army officers clearly loyal to the Republic were rarely trusted, and consequently the new revolutionary militia lacked training and discipline. Its military value was extremely low.’"

"Thus the first major advantage enjoyed by the Nationalists lay in superior military leadership, organization, and quality. The second lay in their complete control of the elite sector of the Spanish Army, the well-trained and equipped units, mostly of volunteers, stationed in Morocco. They numbered 47,000 on paper (33,000 Spanish, 14,000 Moroccans), but their actual effectives were probably 20 percent fewer. Though better led than the Republicans, the Nationlist forces in the peninsula were increasingly outnumbered, generally poorly armed and supplied, and at first not altogether reliable politically in some cases.

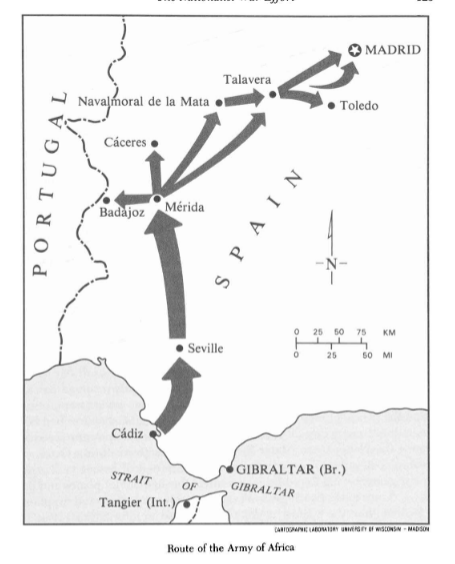

Therefore Francos Army of Africa was the main hope for victory, but as a result of the general failure in the Navy it found itself bottled up in Morocco, unable to cross the straits. With the large cities and industrial zones largely in Republican hands, Mola lacked the strength in the north to move effectively against them. After ten days of intermittent fighting on several improvised fronts, the most important of which was the effort to advance through the mountains north of Madrid with several small columns, he was in danger of running out of ammunition. The Popular Front forces dominated the main sources of supply, and the new wartime government of José Giral, organized on July 19, immediately asked for material from the new Popular Front government of France. Aid was pledged a day later, and the pledge became public knowledge very soon afterward. By that time most foreign observers judged that the rebellion was a failure, and therefore, as J. W. D. Trythall writes, “Francos slogan, “Blind faith in victory, was an apt one. Everybody with his eyes open was giving long odds against his victory.”*"

"On July 27 Mussolini decided to send 12 bombing planes and a small amount of other equipment to the rebels. On the preceding day, Hitler came independently to the same decision, agreeing to send 26 transport planes and other equipment, designed above all to move Francos elite troops to the peninsula. Two special holding companies were created to handle shipments between the two countries.* On July 26 the Portuguese government of Salazar promised full cooperation with the Nationalists, covering their western border.

Even before the first foreign planes arrived, Franco initiated the first airlift in military history with several Spanish aircraft on July 20, flying small numbers of troops across the straits to Nationalist Andalusia. One small convoy managed to make the crossing on August 5, and the Republi- can blockade was broken altogether by the end of September. "

Nationalist Strategy

"Carlos Asensio, who took over some of the advance units on September 21, ruefully observed twenty-five years afterward: “For lack of effectives, our advance turned out to be terribly slow.”'” Armored vehicles were virtually nonexistent, and the Army of Africa often traveled on foot, though it sometimesemployed trucks and buses.

It cannot be said that either Franco or Mola showed much strategic imagination...Mola already held a position that was only about 40 kilometers north of Madrid, yet noeffort was made to transfer any of Francos elite units northward where they might have quickly broken through to the capital. Instead, Franco continued to plod directly ahead, first occupying all of southwestern and west-central Spain, which took six weeks."

"Even when he got nearer Madrid in late September, Franco made no effort at a grand strike that might have quickly overcome a partially unde-fended city. Instead he delayed, to divert a major portion of his limited resources to relieve the Alcázar de Toledo, where 2,000 defenders had withstood an epic siege of more than two months.'' This was typical of Franco’s priorities throughout the war, determined first of all to consolidate his general position before advancing further, attuned to political and psychological symbols, and responding to major commitments of the enemy more than to a rapid and imaginative independent strategy that might have brought the conflict to an early conclusion.

It has been argued that the failure to move on Madrid as rapidly as possible at the close of September may have been Francos major error of the war.'? Discouragement and demoralization among the capital's Republicans was at its height at the end of summer, though whether the degree of disorientation was great enough to have allowed a very small Nationalist strike force to seize a large city in a coup de main can never be known. Franco had on the other hand major strategic reasons for closing his right flank before undertaking the decisive operation of the war, for even after the relief of Toledo his right flank was weakly held and for some months in danger of being turned.

At any rate, when the direct advance on Madrid was resumed in October, resistance stiffened. The first all— Popular Front government, organized the preceding month under the Socialist Largo Caballero, had begun to build a new Republican People's Army whose manpower exceeded that of the Nationalists. Major Soviet supplies arrived during October, creating a Republican armored regiment composed of Soviet tanks and crews, guaranteeing Republican air control through Soviet planes and pi- lots, and once more assuring overall superiority in equipment and supplies."

International aid

"Mussolini at the very least hoped to avoid a leftist regime in the west Mediterranean and probably, more ambitiously, hoped to expand Italian power and influence. Hitler's goals were more limited. He wished to defeat a leftist regime, bring a friendly movement to power, tip slightly the balance of power in the southwest, and probably most important in the later phases, distract international attention from his own actions in cen- tral Europe." This did not preclude the private sale by several German firms of modest arms consignments to the Republic during the early months of the conflict. After making their decisions to intervene separately and independently, Hitler and Mussolini took the first step toward cooperation on August 4, and in fact this mutual concern initiated the relationship that became the Rome-Berlin Axis in October. "

"Thus the first small shipments of German and Italian planes were followed during August and September by modest consignments of conventional arms, and two squadrons of light tanks were organized in conjunction with the Army of Africa. When the first large shipments of Soviet weapons and personnel tipped the balance by early November, Hitler decided on a counterescalation of his own, shipping a whole small German air corps, the Condor Legion of approximately 100 combat planes. It was assembled during November. **"

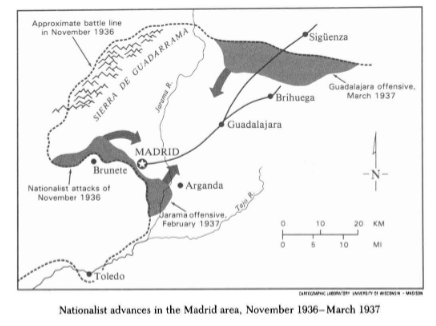

"By this time the shock units of the Nationalist forces were so depleted that the first direct assault on the defenses of Madrid on November 8 was made by scarcely 12,000 troops divided into several columns.”...After November 21, the Nationalists went over to the defensive in this sector. The rebel command was momentarily shaken and Major Castejón, a badly wounded column leader, remarked despairingly to the American journalist John Whitaker, “We who made the revolt are now beaten.”"

"Improved equipment and organization, revitalized morale, and the advantage of numbers and interior lines enabled the new People’s Army to build a successful defense. Indeed, the Nationalist line was stretched so thin by the new year that a determined counterattack by several Republican brigades might have disrupted the entire front."

"Though Hitler decided on December 22 not to expand Germany's commitment any further, the Italian government was being drawn deeper into the conflict. Germany and Italy, having become allies for the first time in their Spanish intervention, had officially recognized the Nationalist regime on November 18, and Mussolini committed Fascist prestige to Francos victory, whatever the cost. Italian air support had helped the Nationalists hold the key Balearic island of Mallorca against Catalan assault,” and before the close of 1936 Mussolini had decided to send Franco not only much more materiel but also a whole Italian artillery corps and several divisions of Italian troops and Fascist Party militia. "

"With Francos best forces momentarily exhausted, the Italian Corpo di Truppe Volontarie (CTV) took the main initiative early in March in the boldest move yet attempted on the Madrid front, endeavoring to strike southward from Guadalajara, northeast of the capital, to cut it off from the east. The resultant Battle of Guadalajara, perhaps the most famous single encounter of the Spanish war, began on March 8. Roads were few and poor and the weather soon turned very bad, handicapping movement. The attempted advance of a Nationalist division farther west was stopped by Russian tanks. Though the Italians gained ground, they failed to achieve a breakthrough and were met with stiff counterattacks. The struggle was broken off on March 14 far short of its major objective. Thanks to the bitter weather and the inadequacy of training, maps, equipment, air support, and leadership among the Italians, and thanks to the aggressiveness of the main new Popular Front brigades, the Republicans had won a major psychological victory.* This was not totally disheartening to the Nationalists, however.” Franco had never asked for the entry of large numbers of Italian troops and resented the independence of the Italian command."

Nationalist conscription and forces

"The failure to seize Madrid during the winter of 1936-37 made it clear that a mass, twentieth-century army would have to be developed for a long war, a project on which the Largo Caballero government in the Republican zone had been embarked since the preceding October. Soon after Franco became generalissimo, his German advisers began to urge him to declare mass conscription. Because of the political unreliability of much of the population, Franco was not eager to do this. Broad conscription measures, however, had been taken by local commanders in certain areas such as Mallorca and western Andalusia, "

"Though a significant minority in the Nationalist zone opposed the regime, most of the middle classes and Catholic peasantry responded effectively to the nationalist appeal. By and large, morale was good and there was widespread determination to defend religion and the national way of life against the revolution and against what was perceived to be a threat of foreign domination. In this even the aristocracy, a privileged and some- times corrupt class, set an example, and the proportion of volunteers from the aristocracy was at least as high as from other strata of society.”"

"For numbers of volunteers and spirit of self-sacrifice, the heroic province par excellence was Carlist Navarre. During the first week of fighting, eleven different columns (mainly of civilian volunteers) were organized in Pamplona, ranging from 200 to 2,000 men each. During the course of the Civil War, Navarre provided 11,443 volunteers for the Carlist militia, 7,068 for Falangist units, and 21,950 volunteers and recruits for the regular Army.* This amounted to a total of 40,461 volunteers and recruits from a provincial population of 345,883—nearly 12 percent of the population, the highest proportion in Spain. Of these, 4,552 died in combat or of wounds (the Navarrese normally forming part of the shock units), a percentage of 13.2, more than double the rate of 5.69 for all Nationalist forces.” On November 8, 1937, in official recognition of Navarre s remarkable contribution, Franco officially awarded the Gran Cruz Laureada de San Fernando, Spain's highest military decoration, to the province as a whole."

"he largest group of foreigners were the more than 70,000 Italian military personnel who served in Spain, primarily during 1937. As many as 10,000 German military personnel may have been in Spain at one time or another (two or three times the number of Soviets), but unlike the Italians, they served in advisory roles as often as in combat. European volunteers were few compared with the Communist-organized International Brigades in the Republican Army. The largest contingent came from neighboring Portugal, whose total has been estimated as high as 20,000, though the only serious study reduces the figure to less than half that.* The second largest group were the French, though the most loquacious were the Irish,” who saw very little combat.

Preparation of a large cadre of reliable officers was crucial. The first step was taken by the Burgos Junta on September 4, 1936, when it decreed organization of a series of courses in Seville and Burgos for the training of alféreces provisionales (provisional second lieutenants). Young men between twenty and thirty years of age, of sound political back- ground, and possessing a professional license or the equivalent of a bachelors degree were eligible. This meant primarily university students or graduates from the middle classes. The training of alféreces provisionales was greatly expanded in October and November, when three new schools were set up. Between the autumn of 1936 and the spring of 1937 hundreds of German military specialists and instructors were sent to the Nationalist zone to provide training."

"During the next two years his bureau, the MIR (Mobilization, Instruction, and Recovery), expanded the number of training schools to 22, with at least a few German advisors in almost every one. In January 1937, the age requirement for officer candidates was lowered to eighteen years, and by the end of the war the program had commissioned 29,023, while approximately 19,700 NCOs were trained in other sections. With the addition of naval and air force officers, the total came to 30,311.*

When the MIR began operating, the Nationalists had already drafted 350,000 recruits. In March 1937 the regime called up reemplazos from 1927 onward and mobilized combatworthy males in the Nationalist zone between the ages twenty-one and thirty-one. The age limit was steadily lowered until by August 9, 1938, the first trimester of 1941, made up of eighteen-year-olds, was drafted. This provided another 450,000 recruits by the beginning of 1939.* From start to finish, the Nationalist forces mobilized well over one million men—the greatest concentration of military manpower in Spanish history."

"For ordinary recruits, basic training was brief, lasting only thirty days. By 1937 medical services were fairly well organized but living conditions remained crude. There were standard problems with lice and petty thievery. Relations between officers and men were formal and highly disciplined, and in general the recruits responded reasonably well. They appreciated the fact that their own commanders provided better preparation, organization, and leadership than existed on the Republican side.

Tactics and performance followed a fairly rigid pattern. Despite an occasional experiment in mobile warfare attempted by German advisors, the larger Nationalist units advanced in a straight line. Superior organization and leadership gave them greater cohesion than the Republicans, particularly on the offensive, though this advantage was only relative. Even in the Fourth Navarrese Division, according to one of its alféreces, some of the old-line regular officers could not read complex field maps. The Nationalist Army never became a first-rate twentieth-century military machine; it won because it held certain advantages over the less effective contingents of the Popular Front."

Republican disorganisation

"The Republican forces generally had the advantage of numbers and materiel throughout the first year of the Civil War, as well as that of usually acting on the defensive. Their greatest liability was failure to overcome their lack of military leadership and effective organization. In forming a new revolutionary Peoples Army during 1937 that used the Communist red star and clenched fist as its insignia and salute, the Popular Front passed from disorganized to organized militia but never altogether to a regular army, even though it had the look and structure of one. Units retained political identities and loyalties that were not overcome. Though the Soviet system of political commissars was introduced, this had only limited effect. Soviet advisors exercised much more influence than did the German and Italian staffs in the Nationalist zone, and largely controlled the Republican Air Force and Navy.

By 1937 a network of espionage and guerrilla groups had been organized behind Nationalist lines by the Soviet NKVD chief Alexander Orlov, who supervised Republican intelligence and counterintelligence activities. Orlov, who had organized Red partisans during the Russian Civil War, wrote:

The Russians regarded Spain as a testing ground for perfecting the Soviet guerrilla science accumulated since the October Revolution and for acquiring new experience. We started from scratch and within ten months [that is, by July 1937] we had 1,600 regular guerrillas trained in the six schools which I organized in and around Madrid, Valencia and Barcelona, and about 14,000 regular guerrillas, who were trained, supplied and led by our instructors on the territory of Franco, mostly in the hills from which they could descend to harass moving enemy columns, attack supply convoys and disrupt communications.”"

"In general both sides collected considerable military intelligence concerning the others plans and development.” The Nationalists had many sympathizers in the Republican zone, and a number of the professional officers who remained in Republican service turned out to be disloyal. In general, however, Nationalist intelligence was apparently the less thorough of the two, for the major Republican offensives of 1937-38 all came as at least partial surprises to the Nationalist command."

Guernica

"For nine months, weak Nationalist forces had manned the irregular lines holding this northern sector in isolation.* Containing most of Spains heavy industry, it was a valuable prize in a longer war of attrition."

"Guernica marked one of the two principal routes of retreat toward Bilbao. The city was a district communications center, and contained three military barracks and four small arms factories. The bombing of cities had been made routine practice during the first week of the Civil War by the Republicans, who on several occasions early in the conflict boasted of the damage done to Nationalist- held cities. There is no evidence of any special experiment or massive terror-bombing. Guernica was a routine target of particular importance because of the circumstances of April 26, but it received no special treatment. Though the chief objectives were the nearby bridge and other transportation and communication facilities, many incendiary bombs were also dropped on the town itself, with the aim of destroying much of the city to block retreat of Basque troops through it. The assault was carried out by 3 Italian medium bombers that dropped almost 2 tons of bombs and by 21 German medium bombers (18 of which were obsolescent Ju-52s) that discharged a maximum of 30 tons. This amounted to no more than a third of the effectives of the Condor Legion, and only one bombing run was made. The bridge remained intact, but many bombs fell within the city, where flames spread rapidly because of the extent of ooden construction, the narrowness of the streets, the loss of water pressure, and the lack of fire-fighting equipment.”

The destruction of Guernica was an immediate embarrassment to Franco and his new government. Rather than admitting the facts and placing them in the full perspective of the war, Nationalist authorities denied any responsibility whatever and charged that the burning of the city was a deliberate act of leftist arson. "

Republican strategy

"After the weather cleared in June, a week of hard fighting sufficed for the occupation of Bilbao, precipitating the collapse of the remainder of the Republican resistance in Vizcaya.” All the while, however, the main part of the People's Army was building up a preponderance of force. Organizational deficiencies prevented it from launching the first major Republican offensive of the war in time to relieve the pressure against Vizcaya, but on July 6 more than 60,000 of the best-trained and equipped troops in the People's Army, supported by nearly 100 Soviet tanks and sizable air units, began an assault fifteen miles northwest of Madrid, near the town of Brunete. It achieved complete tactical surprise, punching a hole through the thinly held Nationalist line almost immediately. Failure to exploit this initial success decisively revealed the limitations of the central sector of the new People's Army. There were few roads, communications became snarled, and the attacking units failed to keep moving. Field offcers let their forces be tied down in frontal attacks or sieges of a handful of fixed positions where the Nationalists had dug themselves in. After the first day, a cautious and uncertain Republican command halted the advance. Nationalists hurried reinforcements in from the north and other areas and their week-long counteroffensive then regained most of the ground lost,* leaving some of the best People's Army units dispirited and exhausted. The People's Army chief of staff, Vicente Rojo, has suggested that a major Nationalist assault against Madrid at that time might have brought the war to a speedy conclusion.*?"

"in this campaign the Republican forces lost 100,000 in prisoners alone. The northern provinces had provided the highest rate of volunteers and some of the best soldiers for the People’s Army, and their loss would never be made good."

"For political and logistical reasons, however, Republican strategy was based on concentration near the major population centers, and in the Zaragoza sector “many soldiers’ had deserted the Nationalists during the first months, leading the Republican staff to consider this a weak point."

Logistics

"Even more important, the war of logistics and supply shifted decisively in favor of the Nationalists during the last months of 1937, as a result of the almost complete success of Nationalist naval warfare, strongly supported by Italy. Nothing better illustrated the greater aggressiveness and superior military leadership of the Nationalist forces than did the war at sea. Despite the naval superiority originally held by the Republicans, Franco had decided immediately after his assumption of the mando único in October 1936 to attack Republican shipping whenever possible."

"By late 1937 both Hitler and Stalin became somewhat more detached from the Spanish struggle. The Soviet regime began to reduce the flow of materiel to the Republic, doubting the prospect of victory and the util- ity of maintaining its previously high commitment, while Hitler observed to his military advisors on November 5 that “a 100 percent victory for Franco” was not desirable “from the German point of view.” Germanys “interest lay rather in a continuance of the war and the keeping up of the tension in the Mediterranean” to distract international concern from cen- tral Europe.

Yet the existing level of German support was maintained,"

Teruel

"Nevertheless, the Republican command believed that it could not af- ford to relinquish the initiative. Learning that Franco planned a major new offensive in the Guadalajara region for early winter, the leaders of the People's Army chose to forestall it with a preemptive move of their own. Nearly 100,000 troops were assembled for the largest Republican effort of the war, though only 40,000 were committed to the first phase of a new offensive east of Guadalajara. Here the front turned sharply north at right angles near the provincial mountain capital of Teruel, in National- ist hands since the beginning of the war. Once more the first assault achieved surprise, breaking through to a depth of 10 kilometers in twelvehours before losing steam. German and Italian advisers urged Franco not to be dissuaded, but to withdraw to a more easily defended line in Aragon so that the main Nationalist forces could proceed with their new Guadala- jara offensive. The Generalissimo, however, remained acutely sensitive to political and psychological factors of prestige. He felt it dangerous to con- cede the Republicans the smallest territorial gain and therefore canceled his own plans, ordering preparations for an all-out counteroffensive. Bitter sub-zero weather, by far the coldest encountered in major operations during the Civil War, impeded realignment, and the Teruel garrison finally surrendered on January 7 after suffering more than 75 percent casualties. This was the first and only time that a Republican offensive managed to conquer a provincial capital. Franco, meanwhile, was roundly criticized by the Italians for “indecisiveness.”"

"The corner of the Nationalist line southeast of Zaragoza lay less than 100 kilometers from the Mediterranean. With his main forces concentrated in this area, Franco decided to undertake a two-pronged advance east and southeast to cut the Republican zone in two. Weak and exhausted Peoples Army units collapsed before the offensive that began on March 7, and major breakthroughs were made at every point of advance. German and Italian armor, supplemented by captured Soviet vehicles, totaled nearly 200 tanks, yet this was not blitzkrieg, for small armored units were used mostly in conjunction with the infantry and hardly at all as independent offensive force. At some points the Republicans were scarcely fighting back; a few of the best Nationalist divisions were semimotorized and in one area advanced nearly 100 kilometers in eight days. "

Late phase of the war

"In April 1938 the collapse of Republican strength in the northeast opened the way for a rapid occupation of Catalonia and the seizure of Barcelona, the current Republican capital, bringing total control of the border with France. It has sometimes been said in Franco's defense that he feared the reaction of France if Nationalist forces, drawing on German and Italian assistance, took over the entire French border area during the tense pre-Munich spring of 1938, "

"The reconstitution of the Peoples Army in Catalonia during the late spring and early summer of 1938 ranks as one of the major achievements of the Republican war effort...As in earlier offensives, the People's Army proved incapable of exploiting its advantage fully, and the Nationalists soon stabilized their line about 15 kilometers west of the bend in the Ebro.”

Tension already existed at Francos headquarters, caused by the resentment of a number of his top generals at the unimaginative and plodding frontal assault against the defenses of Valencia. The Republicans Ebro offensive did relieve the pressure in the south, for Franco once more decided to abandon his own objectives and switch to a battlefield chosen by the enemy. Popular Front propagandists loudly proclaimed that the Ebro effort was an all-out offensive designed to break the enemy, and Franco apparently felt that for political and psychological reasons he could not afford to let the Republicans retain the ground they had won."

"Though local Nationalist counterattacks began in August, it took at least six weeks to complete the full buildup, and even after that the advance was slow. Kindelan has written that this sluggishness was due to the “depressive effect that the Red offensive had on our troops and some of their commanders, producing temperamental aberrations . . . , logistical errors, and exaggerated meticulousness in preparing the operations.” Moreover, the losses of two years of fighting and the problems of staffing a mass army had lowered the quality of Nationalist field officers. In the early phases of the Ebro struggle, “the deficient quality of officers at battalion and company level was evident. . . . Exaggerating a bit, it could be said that every intermediate-level [professional] infantry officer with field experience had died by the end of the second year of the war.””* The artillery was similarly affected, for despite comparatively light losses, batteries that could once have been moved in four hours now required twelve hours to change positions.” The slowing down of Nationalist operations especially infuriated Mussolini, who on August 24 “used violent language in blaming Franco for “letting the victory slip” when it was “already in his grasp. Some of Francos own commanders apparently felt the same way and the Nationalist leadership probably suffered more from internal tension during the late summer of 1938 than at any other point in the war."

Evaluating the war

"The most thorough and objective study concludes that the Republicans lost 554 ships of all types, 144 of them to Italian and German (primarily Italian) action, and that 106 foreign ships bearing Republican supplies were also sunk, 75 of them by Italian and German action. By contrast the Nationalists lost only 31 ships of all types, 9 of which were apparently sunk by Soviet action.”"

"Franco was as successful as the Republicans were unsuccessful in maintaining his independence of command. There were only very occasional direct interventions limited to specific instances, such as the order given by Mussolini in mid-March 1938 for Italian planes based on Mallorca to carry out several terror raids of intimidation against Barcelona (raids that, according to the German ambassador, left Franco “pale with anger). Otherwise, Mussolini merely fumed in Rome about the slowness and alleged ineptitude with which Franco conducted his war.* Relations with Nazi Germany were much more difficult in every way.

On the one hand, the German Fiihrer was more detached than Mussolini and less willing to make major commitments of materiel, while on the other, German representatives were pushy and meddlesome, did much more to interfere with domestic politics, and steadily increased their pres- sure for major economic concessions in return for war supplies. "

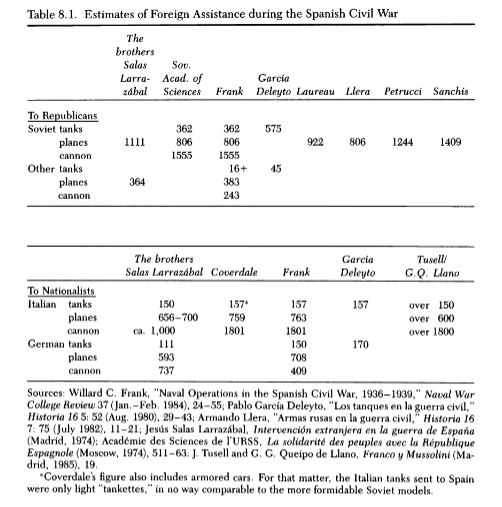

"Unlike the Republican government, which paid for almost every bit of materiel that it received from the Soviet Union and elsewhere with gold (virtually liquidating the gold reserves of the Bank of Spain), Franco obtained the great bulk of his arms and other supplies on credit. The most thorough study indicates that Italy, the main supplier, provided $355 million worth of military goods and Germany a total of $215 million, while $76 million came from other countries. Thus the Nationalists obtained approximately $645 million of materiel in toto, compared with aggregate Republican expenditures of approximately $775 million. The Italian materiel was provided almost entirely on credit, which was in turn paid off by the Nationalist government over a long period of nearly thirty years until the last lira had been returned. The Germans were more demanding, insisting on hard currency as much as possible and major raw material concessions. During the final year of the conflict the Nationalist government was able to pay about $300,000 to each of its Axis suppliers in hard currency.”

The German government was particularly interested in making a major penetration of the Spanish mining industry, whose raw materials could be of prime importance for German military production. "

"The first real German breakthrough came in June 1938, when Franco felt compelled to allow establishment of a new German mining company that would hold more shares in mining ventures than was normally permitted foreign groups by Spanish law. This concession was extended further in November, when to insure German support for the last phase of the war, the German share in five Spanish mining groups was permitted to increase to between 60 and 75 percent.’

The Munich crisis raised the direct possibility of a general European war that might have disastrous consequences for Nationalist Spain. Franco immediately made it clear that he had no intention of being dragged into a German war, assuring both Britain and France of his absolute neutrality in the event of a general conflict. This galled both Rome and Berlin, and yet the logic of such a step could not be totally denied. In turn, Franco encountered no difficulties with France early in 1939 as his forces occupied all northeastern Spain."

"The Republicans not only received more tanks than did Francos army—by one scholarly calculation nearly twice as many—but the quality of the Red Army armor that they received was superior, in some cases by a wide margin, and the first shipments were accompanied by Soviet crews who took the tanks directly into action. The complaint registered by some People's Army veterans that the Soviet materie! was worn out or inferior does not seem to be justified in most cases. The Soviet planes serving on the Madrid front clearly outperformed German and Italian fighters until the first Messerschmitts arrived, Soviet artillery wasrather better than the Italian pieces that provided most of Francos equipment, and Soviet tanks were more heavily armored and possessed greater firepower than any of the German and Italian models."

"A prime characteristic of the Spanish Civil War, both politically and militarily, was that what was actually taking place was often misreprsented as something that it was not. False political representations had their counterpart in false, misleading, or incomplete military conclusions. Thus there has been considerable exaggeration about the military experimentation supposedly carried on during the Spanish war and the lessons derived from it. Tactics and materiel were a unique blend of World Wars I and II. Both sides obviously had the opportunity to employ a number of minor military innovations, such as more rapid-firing new weapons, but none of these were revolutionary. For the purposes of World War II, the conclusions drawn by European armies were perhaps more inaccurate and misleading than they were pertinent and helpful.’

The Germans profited most, but even then only partially. The most significant new factor demonstrated in Spain was the effectiveness of Ger- man tactical air support, which played a major role in several key Nationalist victories. And it was in Spain that German fighter pilots first developed the standard western “Finger Four’ formation, later also used by the RAF and USAF. Many of the German aces of the early phase of World War II got their first combat experience in Spain, and the Luftwaffe developed new night flying expertise. The general conclusion drawn by the Luftwaffe was that strategic bombing of cities and industry deserved much less emphasis than did tactical bombing in support of land operations, an emphasis that would cost the German war effort dear from the autumn of 1940 on."

"The partially anachronistic character of the Spanish war, together with the relatively superior performance of the Nationalist troops using Italian weapons, lulled the Italian leadership, which never seriously planned or prepared for involvement in a massive world war, into a false sense of complacency. Even the frustration of their lightly armed infantry in the face of Soviet tanks at Guadalajara made scant impression.

Nor did Soviet military leadership prove demonstrably more sagacious in learning from the Spanish conflict. Though they did grasp the importance of increasing the strength of their tank armor, they were already headed in that direction anyway, whereas the limited utility of armor in Spain further convinced them that a tactic of dispersal among infantry units—the very opposite of the German massed armored blitzkrieg—was the appropriate tactic for European war. Similarly, the disastrous failure of Soviet aerial tactics in Spain—which emphasized group combat and the defensive over individual tactics and the offensive—produced scant change in their approach until after 1941."