Chapter 20: Continuity and Reform during the 1960s

"In his later years, Francos personal appearance became more gentle and even rather kindly. He normally appeared in conservative business suits and projected the image of a fragile, sometimes gentle grandfather— an appearance accentuated by his quiet, courteous manner. In the final phase of his life, this air of mild-mannered, benevolent patriarch presented an ironic contrast to the military style and fascistoid bombast of the early years of the regime.

The aging and decline of the Caudillo underscored the uncertainty of the political succession, for which the heirs of the royal family remained primary candidates. "

"The Generalissimo continued to completely exclude Carlist candidates from consideration on the grounds that their direct line had ended and that the Carlists had no appropriate candidate who was Spanish and known to the Spanish public."

"Franco began to lose any lingering hope of a full accommodation with Don Juan and turned his attention more and more to his son...the Asturian law professor Torcuato Fernández Miranda, was placed in charge of coordinating his further studies and administrative visits to learn more of the functioning of various branches of the government. Miranda was a veteran theorist of “organic democracy” as it had evolved under the regime* and the author of several political textbooks. He was a staunch formal de- fender of orthodoxy, later writing that “the ‘Succession must be continuity. ... The King. . . must be the incarnation of the historiconational legitimacy which the Spanish state created by the eighteenth of July in- carnates.”* In fact, the rhetorically sinuous Miranda, with his sharp wiz- ard's face, was one of the wiliest figures in the regime, fully cognizant of its manifold shifts of emphasis. He was alert to the opportunity that Juan Carlos represented and tried not only to indoctrinate him but also to pro- vide a broader political education within the framework of the regime's evolution. The relationship thus begun between the two in the early 1960s would become decisive for the future of Spain after Francos death. Meanwhile, in recognition of Juan Carloss status and growing maturity,"

"Franco was generally quite pleased with Juan Carlos and seemed convinced that his ploy was working. Snide comments in Madrid society that the Princes smiling good nature and shy manner bespoke naiveté and limited intelligence failed to impress him for he knew better. When asked his reaction to one of the personal visits of Juan Carlos, he replied: “Magnificent, and of course the rumor circulated by his enemies that he is not bright is unfounded. Not at all, since he is a lad who talks very well and thinks for himself and not just what he may hear from his friends or fol- lowers. I do not believe that he is dominated by his father in political af- fairs.”® Even so, the Caudillo showed no inclination to recognize Juan Carlos or anyone else as his successor."

Slow Recrudescence of the Opposition

"Having reached a low point in the 1950s, the domestic opposition became more active by 1960 and slowly but steadily expanded during the following decade. For the first time in some years, the number of arrests began to rise, though the change was not dramatic, and the tendency was for prosecution to become increasingly lenient. "

"expanding industrial labor force showed increasing signs of militance. A major strike wave began in Asturias during April 1962 and in the following month expanded, spreading through the Basque provinces and the Barcelona region.*” A new style of labor opposition was taking form in the clandestine comisiones obreras (worker commissions) being organized by Communists and dissident Catholic social activists, sometimes jointly. The first fully developed commission was formed in an Asturian mine in 1958, and by 1962 such groups were beginning to appear in other parts of the industrial north.' The commissions were not intended to be organized trade unions but ad hoc factory committees to serve as representatives chosen directly by informal groups of workers themselves. In coming years they would coexist with and in some cases overlap with the official Syndical Organization, in which Communist activists energetically participated at the lowest level.

Though a “state of exception’ was declared in three industrial provinces in May, 1962, the government's response was the softest ever taken toward strikers to that date. Leaders of the Syndical Organization were hearing more frequent demands for “authentic unions’ and had themselves proposed several reforms that were blocked in part by Fernandez Cuesta and the old guard in the Movement. In an unprecedented step, Solis Ruiz, head of the Syndical Organization, went to the industrial centers to talk to leaders of some of the strikers. A number of workers were either arrested or fired but not as many as in previous strikes, and the special powers of repression reenacted by decree two years earlier were for the most part not used. A new law of July 1962 provided for worker representatives in the councils of industrial plants and for management representatives on workers’ syndical committees,” while a big jump in the minimum wage was enacted the following month. At the same time, the next northern strike wave during the following year was repressed somewhat more rigorously.

A new opposition front began to emerge from what would have seemed one of the least likely groups, the clergy. The massive generational shift within the Spanish clergy during the preceding two decades that produced an influx of new young priests reconstituted the priesthood with younger clergymen who were particularly susceptible to the new currents of liberalization coming from abroad and from the international Roman Catholic Church."

"The beginning of clerical oppositionism may be formally dated from the letter of May 30, 1960, signed by 339 Basque priests to protest the ab- sence of freedom and self-determination among the Basque clergy and in the Basque provinces generally."

"Nonetheless, the only notable gesture of organized political oppositionduring the first half of the decade was what the regimes propagandists called the contubernio de Munich (cohabitation or mesalliance of Munich), in which a sizable number of moderates representing both internal andexternal opposition groups met in the Bavarian capital from June 5 to 8, 1962. This represented an effort by diverse opposition elements to dem- onstrate that the Civil War was indeed over and that both moderate left and moderate right could meet together, with 80 of the 118 signatories of the final document, led by Gil Robles and Ridruejo, coming from within Spain. The meeting occurred four months after Spains first petition to enter the European Common Market, which was likely to be rejected for political reasons, and it was thus designed to dramatize the fact that only different leadership and a democratic system could bring Spain into the new international community. The participants by no means agreed among themselves, for the veteran Salvador de Madariaga and other emigrés sought some sort of international pressure against the regime, a tactic not supported by representatives of the internal opposition. They all signed an agreement on the internal changes needed in Spain before it could expect to make a successful application to enter the Common Market. This action was not necessary to freeze the eventual response to the Spanish petition, but it obviously did not help, and subversion of Spain’s inter- national relations thus became the technical basis for the action taken against members of the internal opposition on their return. On June 8, article 14 of the Fuero de los Espanoles (concerning freedom of residence) was suspended for two years and returning participants were temporarily confined in the Canaries. "

"The next few years were in fact quiet ones, the most notable event of 1963 being the execution on April 20 of the clandestine Communist leader Julián Grimau for alleged crimes involving torture and murder committed as a Republican police officer during the Civil War. (“Ordinary ” Civil War political crimes were covered by amnesty, but not “major” offenses or delitos de sangre.) A Communist central committeeman, Grimau had been apprehended after he reentered Spain, and his execution became an international cause célébre, even the Queen of England joining those who attempted to intercede. Despite the adverse publicity abroad, Franco was implacable in such cases.

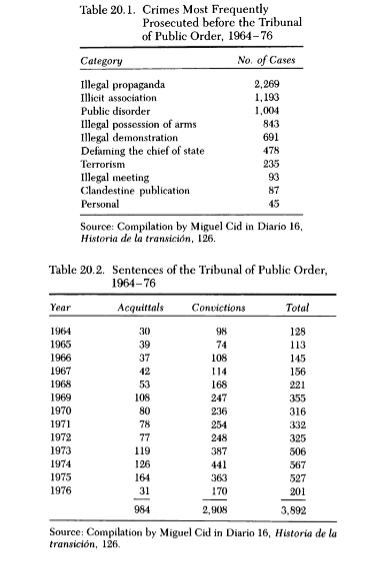

This affair nonetheless helped to produce one change, coming as it did on the heels of an investigation by the International Commission of Jurists. The results of the investigation were published late in 1962 as The Rule of Law in Spain, and severely criticized limitations on civil rights, particularly the continued authority of military courts as distinct from standard civil courts.'* The Council of Ministers first discussed the desir- ability of terminating military jurisdiction in December 1962. One year later, on December 2, 1963, a new law established a Tribunal of Public Order, composed of civil judges, to deal with most categories of nominal political subversion or political crime. "

The Reforms of the 1960s

"When after the Munich affair he decided on a partial renovation of the cabinet, the direction chosen was that of a further apertura or opening, though always along carefully controlled lines that would hold the monarchists at bay.

Foremost among the changes in the partially new government of July 10, 1962, was the appointment for the first time of a vice-president of government and lieutenant to Franco himself in the person of the veteran Munoz Grandes,"

"In November 1960 a petition was signed by many leading Spanish writers and intellectuals— including even a veteran cultural luminary of the regime like Pemán—asking for more careful regulation of the censorship, along with juridical guarantees and public identification of responsible censors. "

"The new minister of information and tourism was the forty-year-old Manuel Fraga Iribarne, "

"The new cabinet, which with minor changes would last for seven years, harbored two different somewhat fluid and overlapping sets of rivalries. One was between the technocrat-monarchists, supported and to some degree led by Carrero Blanco, and the so-called Regentialists (or at least lukewarm monarchists), to some extent led by Muñoz Grandes and including Solís Ruiz and the new navy minister, Pedro Nieto Antúnez, a former naval aide of the Caudillo. Fraga, though basically a supporter of the monarchist succession, tended to be allied with the Regentialists. The second rivalry was between reformists and those who wished to avoid major internal political change while concentrating on economic development. The reformists were led by Castiella, the foreign minister, Fraga, and Solís (though the three did not necessarily agree among themselves as to the character and content of reform) and were “frequently aided by Romeo Gorría and occasionally by López Bravo.”” They also drew some support from Muñoz Grandes and Nieto Antúnez, while Iturmendi (Justice) and Navarro Rubio (Finance) fluctuated. For the most part on the other side were Carrero Blanco, Alonso Vega, Vigón (Public Works), and to a lesser degree Martín Alonso (Army), who were more concerned with the succession than with internal reform. That was also the position of López Rodó, though he did not oppose all the goals of the reformists."

"Carrero was aligned with the technocrats, who did not seek immediate reform as much as a kind of technocratic depoliticizing of the system. Spains political future would be assured not by reformist or quasi- Falangist ploys but through the full institutionalizing of the monarchy. They sought to guarantee the succession by having Juan Carlos recognized as heir while Franco still lived, meanwhile striving more and more to dismantle the Movement. The result would be a progressive, modern, and rationalized authoritarian structure guided by technocracy and crowned with monarchy. López Rodó, the economic commissar of the plan and key figure among the technocrats, has been described with little exaggeration as seeking a “symbiosis between Catholic values, an authoritarian political system, and the American way of life.”"

"These complex rivalries in the new government had little to do with the classic political “families” of the regime in earlier years. The original sectors of old-guard Falangists, Carlists, doctrinaire monarchists, semiauthoritarian traditionalist Catholics, and right-wing generals had mostly fallen by the political wayside. The various institutions of the regime were still full of survivors from all these groups, but they were rarely any longer at the top, for their ideologies no longer represented options for an increasingly industrialized country in the social democratic western Europe of the 1960s."

"The new government of 1962 quickly introduced a certain change in public style. The new ministers emphasized personal contact with highly diverse groups and segments of society. Unlike their predecessors, they were increasingly on the move, traveling through Spain and even abroad,"

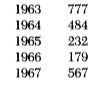

"The disturbances of 1962 encouraged Solís to proceed with limited re- forms in the Syndical Organization. An amendment to the penal code in September 1962 freed labor actions “for nonpolitical ends” from prosecution, though at no time would the regime ever legalize strikes as such. According to the Syndical Organization, the following number of labor actions took place without prosecution during the next five years:™"

"In preparation for the next local syndical elections in 1963, workers were in some cases allowed to hold meetings entirely on their own in syndical offices, and in the following year for the first time separate commissions representing workers and employers were formed within the syndicates to negotiate wages and working conditions.” Yet so many oppositionists were elected that in a later series of crackdowns and combouts, between 1963 and 1966, about 1,800 low-level syndical officeholders would be fired from their factory jobs.” Similarly, all strike actions deemed political were still repressed in varying degrees by the authorities.”"

"On April 1, 1964, there began a major propaganda campaign in honor of the “twenty-five years of peace,” marking the quarter-century since the end of the Civil War...Nevertheless, the relatively hostile attitude of the Common Market caused discomfort, providing further incentive for the regime to make renewed efforts to give its authoritarian “organic democracy” greater credibility in western Europe. "

"During 1964 Solís Ruiz made increasing use of the phrase “political development, * and that summer the Movements National Delegation of Associations moved ahead with a vague project concerning the hermandades (“brotherhoods” of political orientation) first proposed in the Arrese projects of 1956, and began to sketch drafts for the introduction of some sort of “political associations’ within the Movement. Such associations were not to be political parties but simply expressions of several diverse elements in the Movement. "

"Four different groups in the cabinet concurrently prepared their own reformist proposals. While Solís and Fraga worked on separate plans, the foreign minister Castiella had his own pet reform and in September 1964 presented to the cabinet a proposed draft for a new law of religious toleration which he deemed highly advantageous to the regimes foreign relations. Meanwhile, López Rodó and his allies further revised their original sketch for a general new Organic Law which Carrero Blanco handed to Franco on November 25, 1964.

The Caudillo remained skeptical, fearing innovations that might restrict the government's authority or open a dangerous Pandoras box of

political novelties. Even though the draft of the proposed new law of associations within the Movement carefully avoided any appearance of introducing real political parties, to Franco it smacked of that danger and he ordered it withdrawn. "

"During the following month Fraga Iribarne scored the first triumph of the new cabinet, gaining approval of his new press law over the objections of Carrero Blanco and Alonso Vega. He has recorded Franco as conceding reluctantly: “I do not believe in this [new] liberty, but it is a step required for many important reasons. And furthermore I think that if those weak governments at the beginning of the century could govern with a free press, amid that anarchy, we will also be able to get along. ® After further polishing, the final version was approved by the government in October and subsequently sent on to the Cortes, which eventually ratified it on March 15, 1966. Two weeks later prior censorship formally ended. The argument behind this reform was that contemporary Spain had become much more literate, cultured, and politically united than its predecessor a generation earlier, and that Serranos old legislation was no longer appropriate. Censorship would henceforth be “voluntary,” and no official guidelines would be imposed (though many informal ones would be laid down). Publishing enterprises would also be free to name their own directors rather than having to gain ministerial approval as before. A variety of sanctions, such as stiff fines, suspension, confiscation, or even arrest, could still be imposed on those publishing material damaging to the state, religion, or general mores, and any editor in doubt was invited to submit preliminary material for consultation.”

This certainly did not establish freedom of the press, but it considerably eased the restrictions and boundaries on what might be published and opened the way for general liberalization and expansion. Newspaper circulation increased from less than 500,000 in 1945 to 2,500,000 in 1967, and the 420 publishing firms of 1940 had grown to 915 by 1971. In 1970 Spain published 19,717 titles, the fifth highest total in world, amounting to more than 170 million books.“"

"Routine political infighting continued, as was Francos wish. The primary duel was that between his two principal surrogates, Carrero Blanco as minister subsecretary of the presidency and Muñoz Grandes as vice-president of the government. It was an unequal contest, given Muñoz Grandess severely declining health and incapacity for effective intrigue."

"In November 1965 the new justice minister Oriol was able to declare on television that Spain had the second lowest prison population in the world. This was technically correct because of the remarkably low civil crime rate (well below that of most democracies or Communist regimes), but as political penalties were lessened, dissidence increased. On March 9, 1966, there occurred the capuchinada in Barcelona, in which a Democratic Syndicate of Students was organized by university rebels in a Capuchin convent. Two months later, 130 priests marched in the streets to protest the use of torture by the political police. An effort was made to counter unrest by organizing a series of visits by Franco to Catalonia in June. This was one of the last of his grand triumphal tours, for his energy declined as he neared seventy-five, but the customary crowds were assembled and by official standards the visit came off well."

"The Organic Law reconciled various inconsistencies among the six Fundamental Laws (the Fuero de Trabajo, the Law on the Cortes, the Fuero de los Españoles, the Law on the Referendum, the Law of Succession, and the Fundamental Principles of the National Movement) and eliminated or altered certain lingering vestiges of fascist terminology. It separated the functions of the president of government (prime minister) from those of the chief of state, and modified secondary details of the Law of Succession while accentuating somewhat the institution of monarchy."

"Rather than being the real opening sought by some reformists, the Or- ganic Law represented the final readjustment of the system during the phase of Francos life when he was rapidly losing physical and political energy. No basic changes were introduced, thus maintaining the struc- ture and mechanisms on which the regime had long rested. An answer to the key question of the succession had not been significantly advanced beyond the formula of 1947, so that the specific choice of a successor or the option of a neo-franquist “regency remained (even though Franco did nothing personally to encourage the latter alternative)."

"All this amounted to much less than the “new constitution’ promised in the subtitle of a booklet released by the Ministry of Information for the referendum campaign, but the Organic Law and lesser related measures completed the legal structure of the state and would be described, together with the Fundamental Laws, as comprising the “Spanish constitution.” Critics suggested that the regime had lost perhaps its last major opportunity to secure genuine popular support for a serious liberalization of the system. That is most doubtful, since Franco made it abundantly clear that he had no intention of ever permitting basic alterations that might weaken what he termed in 1967 “a modern state with authority.” He fully realized that it was one thing to liberalize policy and quite another to liberalize the basic structure of an authoritarian system, which would then rapidly erode altogether."

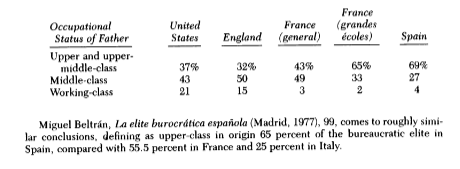

"The system of the late 1960s was beyond all doubt more open, moderate, and responsive than that of ten or twenty years earlier. Though the Cortes never became a parliament and never gained the right to initiate legislation, its members became slightly less timid and occasionally criticized aspects of legislation proposed by the government or even carried through a few minor changes.* Membership remained oligarchic in the extreme, about half the procuradores always being higher state functionaries who held other positions as well.* Turnover was about 40 percent from one legislature to the next,” the most extensive changes coming in 1946 (when National Catholicism came to the fore), 1958 (when the new economic leadership and Solíss takeover of the Syndical Organization brought in new cadres), and 1967, with the slight liberalization of representation. Some of the new family representatives made brief gestures of independence in the next legislature. Unable to get an adequate hearing in the regular chamber, they temporarily formed a rump Cortes viajeras or transhumantes (“travelling Cortes”) until their informal meetings were prohibited by the minister of the interior in September 1968.

The state administrative system also remained relatively elitist. Those who played the leading roles in it came from proportionately higher social background than was the case in most other western countries, with the partial exception of France.” Technical competence on certain levels increased significantly during the 1960s, but personal influence and clientelism remained powerful factors, though in a diminishing degree, to the end of the regime."

"With reformism at an end, the late 1960s were a time of mounting op- position and disorder within the universities and the industrial north. The opposition shadow syndicates, the Comisiones Obreras, were strong enough in several districts to make little effort at concealment, while the two largest and most politicized universities, Madrid and Barcelona, were in a state of constant uproar that would continue with only momentary remission until Francos death. Various faculties were periodically shut down altogether, and henceforth it would be unusual to complete a full academic year without partial closure. Despite intermittent crackdowns, the police were carefully restrained in the degree of repression they were allowed to exercise in the universities. This provoked strong criticism from the ultraright, while leftists took it as a sign of the weakness and senility of the regime, unable to apply the police pressure of earlier years. Franco observed on March 23, 1968, “Many leftists say that we are in the time of the fall of Primo de Riveras government or of Berenguer. They are completely wrong and confuse the serenity of the government with weakness. With his constant awareness of the parallel experience of Primo de Rivera, Franco may not have wished to repeat the policy that united the universities in a solid phalanx against Primo's regime. At any rate, he was on record as having directed the police to go easy, though the minister of education, Lora Tamayo, soon resigned because of conflict with the minister of the interior, Alonso Vega, who directed the repression.® "

"It was not the laxness of the police that produced the rebelliousness of university youth, but the broad changes in society and culture during the previous decade. The secularization that had suddenly become so marked had its ideological counterpart, for, even though the regime’s own ideologists followed Daniel Bell in announcing the “twilight of ideologies” ® and urged Spaniards to concentrate on economic advancement, students and the younger intelligentsia, now in much closer contact with western Europe than a decade earlier, discovered a new materialistic ideology in the neo-Marxist ideas which they imported en masse from France and Italy. The new Spanish-style marxismo cañí (“gypsy Marxism’) amounted to no more than a transcription of foreign ideas with scant elaboration or originality, but it provided a mental framework congenial to the new intelligentsia growing up in a suddenly materialistic and semiaffluent society still subject to political repression. Spain, which had never had a real Marxist intelligentsia during the revolutionary generation of the 1930s, began to acquire a second-hand one in the late 1960s.

For the new vice-president, this scandalous state of affairs was due to the disastrously libertine character of the Press Law of 1966 and Fragas indulgent direction of the Ministry of Information. In a memo to Franco of July 10, 1968, he detailed:

The situation of the press and the other organs of information must be corrected from the inside out. This is producing positive moral, religious and political deterioration. The windows of all the bookstores and the stands of the Book Fair are crowded with Marxist works and the most licentious erotic novels. Moreover, the growth of immorality in public entertainment has been tremendous in recent times. The damage being done to public morality is grave and we must put a stop to it. . . . I greatly fear that the present Minister of Information is incapable of correcting this state of things.”

Criticism from within the government by Carrero and López Rodó of what was seen as Fraga’s dangerous tendency toward reformism led the minister of information to introduce new legislation transmitted to the Cortes restricting information about material designated as official secrets. "

"The government responded much more sharply to mounting labor unrest and nationalist agitation, especially the latter, in the Basque provinces. The new Basque extremist organization, Euskadi ta Azkatasuna (ETA; Basque Land and Liberty), turned to violence in August 1968 with the retaliatory assassination of the head of the political police (Brigada social) in Guipúzcoa. This provoked a severe crackdown which soon brought the arrest of many ETA members and temporarily restricted its activities greatly. A new decree once more broadened the jurisdiction of military courts over political offenses (which had been reduced five years earlier). Continued disorder in the universities and unrest in the Basque provinces led to declaration of a legal State of Exception for two months between January 24 and March 22, 1969. It was followed a few days later, however, on April 1, thirtieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War, by a final and conclusive amnesty for those few still under legal sanction oliable to prosecution for their activities during the Civil War, though this measure still did not bring military pensions for disabled Republican veterans nor rehabilitation of teachers and civil servants fired in 1939"

The Movement in Suspension

"On ceremonial occasions the Caudillo reiterated to Movement members that he was with them and that the organization was still essential to the regime, insisting that “the Movement is a system and there is a place for everyone in it.”% Later in 1967 he would avow that “If the Movement did not exist, our most urgent task would be to invent it.”"

"For many years the Movement admitted no decline in numbers. The 1963 report of the National Delegation for Provinces declared a membership of 931,802 militants,% roughly the same as for every year since 1942, but there was strong suspicion that the names of inactive members were never removed from the lists. The Sección Femenina had reported only 207,021 members for 1959, scarcely more than a third of the total of two decades earlier, but still only a little less than the number of women affiliated with Catholic Action* (though the latter's statistics were more reliable). The reality was quite different, however, for active members in the Movement were relatively few, and in many local districts individual sections had become moribund. A special report of May 19, 1958, that apparently reached Franco analyzed the the organization of the Movement in fourteen northern provinces (including some such as Valladolid in which it had once been very strong) and found the infrastructure uniformly weak.”"

"The most severely eroded of all the Movement institutions was the SEU, its university student syndicate...The SEU was officially dissolved on April 5, 1965. The elite youth group of the Movement, the Guardias de Franco, was also in decline, but as an expression of the hard core it managed to maintain its organizational structure more effectively.”"

"For camisas viejas, the “Opus ministers’ represented a “new right” who were selling the Nationalist birthright for a mess of foreign investment pottage, and at one Movement meeting in Madrid in June 1964 they accused the technocratic government of killing the spirit of the Eighteenth of July. In April 1966 Franco complained of these criticisms, lamenting that “the only newspapers who do not say what their owners want are those of the Movement.’ ” "

"A small minority went even further and was still capable of occasional public outbursts. On November 20, 1960, at the annual commemoration of the death of José Antonio—now held at his new burial site in the Valle de los Caídos—a young militant shouted “Franco, you're a traitor!,” bringing his immediate arrest and five years in prison.” A new current of “dissident Falangism” had emerged at the end of the 1950s in the Guardias de Franco that sought to recover the original doctrines of José Antonio, Ledesma, and Hedilla. This led to the formation in Madrid during 1959 of the first of the semidissident “Círculos Doctrinales José Antonio” under the leadership of Luis González Vicén, sometime leader of the Guardias and still a member of the National Council of the Movement. He lost the latter post in 1964, however, and in 1965 was succeeded as head of the Círculos Doctrinales by Diego Márquez Horquillo, under whose leader- ship they expanded to seventy local sections the following year, in some cases including separate youth, labor, or student groups. This was the largest neo-Falangist organization, but the weaker the official Movement became, the more tiny dissident neo-Falangist groups began to proliferate, half a dozen others being founded before the close of the sixties,”? each more insignificant than the last.

By the mid-1960s only two possibilities remained to the leaders of the Movement: one was to enhance the role of the Syndical Organization, as Solís Ruiz attempted to do, and the other was to try to revive the Movement by acquiring for it some sort of new representative function. Latin American models were vaguely invoked, for an expanded state syndicalism suggested a parallel to Peronism, whereas a more open and representative hegemonic party that encouraged semipluralism within unity raised the specter of the Mexican PRI. In fact, neither alternative was feasible. The Fourth Syndical Congress held at Tarragona in May 1968 was to have reflected the development of a more powerful and influential Syndical Organization, but by that time it had become painfully clear that the system could never achieve authenticity or even the control that it had once had. Not only did it not determine the workers opinions, but it was becoming increasingly unable to control their collective action."

"There remained the intermittent debate that had gone on since 1957 over whether the old form of the Movement as “organization” should give way to a new form of the Movement as a broader “communion” of Spanish society that would guarantee its future not as a single party but as a broader multicurrent channel for participation and representation. "

"The only remaining option was to broaden membership and participation through the ploy of “associationism,” a concept toyed with for a decade. Some lip service had been paid to this in the Organic Law of the State, which declared that one of the goals of the National Council was to “stimulate authentic and effective participation of national entities” and “the legitimate contrast of opinion.” Therefore a new Organic Statute of the Movement was planned in the last months of 1968 to redefine its functions, terming it “the communion of the Spanish people in the Principles of the Movement,” to imply broader participation than that of a single- party membership. Rodríguez Valcárcel's proposal to grant the Movement a massive budgetary increase for political and organizational work and control over propaganda and ordinary state jobs was quickly vetoed, perhaps by Franco himself, and attention focused on article 15, which raised the possibility of “associations” that might be legitimized “within the Movement” for the “legitimate contrast of ideas.”"

"A small group in the old guard, led by Fernández Cuesta, opposed any sort of “associations” as opening the door to the return of political parties, but the statute was approved by the National Council in December 1968"

"Ultras asked aloud “What is the difference between a political association and a political party?” but the new “Anteproyecto de Bases del Régimen Jurídico Asociativo del Movimiento” prepared during the spring of 1969 seemed to bring that danger well under control. The new statute on associations that was approved unanimously by the National Council on July 3 defined them as “associations of opinion” whose organizers would have to collect 25,000 signatures in order to register them legally. The National Council would have complete control over their legal authorization, and there was no specification of the goals or functions of such associations should any ever be authorized. Once more a measure toward aperturismo and greater participation was made so limited in practice as to frustrate any serious reform. Moreover, the statute was never approved by Franco, who had serious doubts about going even that far.

With each passing year membership in the Movement simultaneously aged and shrank. A check of membership records indicated that in Lérida province in 1965 85 percent of the affiliates were more than forty-five years of age, while in 1974 the average age among Madrid members was at least fifty-five. Though a few new members were gained every year (27,806, for example, in 1969), they did not compensate for those who dropped out or died, and came mostly from the semirural Catholic and conservative provinces of the north.*"

Foreign Policy in the 1960

"Spain grew ever closer to western Europe in economics and culture, even though the regime would never become politically acceptable to most of the west European democracies.

Franco always opposed the notion of a united Europe and publicly attacked “Europeanism” as late as 1961. Yet that same year Britain, Den-mark, and Norway all applied to join the European Economic Community, and even Greece made an agreement of association. When the EEC came up with a common agricultural policy that would hamper Spanish exports at the beginning of the following year, Franco saw the handwriting on the wall and authorized Spains application to join the Common Market as well. The EEC members persistently dragged their feet, largely for political reasons, and Franco was in no hurry to enter, realizing that it would require massive structural readjustments in Spain. "

"Though Franco was pleased with the American relationship for the political reinforcement and military security that it provided, he considered Americans “infantile” and observed that he would have preferred the British to lead the western alliance. He criticized the Kennedy administration for its irresolution and clumsy handling of the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and harbored the notion that Washington had erred in not “unleashing” Chiang Kai-shek against the Chinese Communists.” Yet his reply to Lyndon Johnson (in response to a message explaining the new American initiative in Vietnam in 1965) urged caution, shrewdly observing that it would be difficult to win such a contest completely in military terms and that the political and military problems involved were probably too complex for a simple solution.* The Spanish leadership hoped for more favorable terms when the initial ten-year pact with the United States expired in 1963, for Communist Yugoslavia had begun to receive aid at the same time without providing any direct quid pro quo, and over a period of twenty years would obtain more aid from the United States than would Spain."

"Castiella’s display of greater independence was thus calculated to exact a higher price.“ NATO overflights across Spain to Portugal were restricted, and an effort was made to establish a special relationship with France. Madrid generally enjoyed more favorable contact with De Gaulle's Fifth Republic than with its predecessors,"

"In 1964 the regime hired the publicity firm of McCann-Erickson (which held the contracts for Coca-Cola and Old Gold cigarettes) to improve its image in the United States.” The conviction that the assistance provided and the risks run on behalf of collective security were disproportionate was reinforced by the Palomares incident of January 17, 1966,"

"The regime persisted in its efforts to maintain a special relationship with Latin American countries. In 1965, as financial circumstances im- proved, it made a certain amount of money available for development loans, hoping not to be totally outdone by the United States’s Alliance for Progress. Spanish diplomacy was surprisingly friendly to Fidel Castro, though relations were temporarily suspended in 1960 following an inci- dent in one of Castros television marathons to which the Spanish ambassador responded in person at the Havana television studio. Franco naturally supported the United States during the Cuban missile crisis, but commercial relations with Cuba were resumed in 1963. Favorable commentary on the Cuban regime was occasionally allowed to be published in Spain, and Iberia, the national airlines, maintained a direct flight to Havana.” Spanish diplomacy also cultivated cordial relations with Third World countries at the United Nations, successfully angling for their support on the Gibraltar issue."

The Gibraltar Question

"During Britain’s dark summer of 1940, London indicated that it considered the future of “the Rock” to be negotiable, echoing a line first used during earlier difficult moments of the eighteenth century. Needless to say, nothing more was heard of such a disposition after 1945. By that time the population had come to be heterogeneous in the extreme, enjoying local self-government on a democratic basis (something obviously not available in Spain) and a higher standard of living than the Spanish norm.

Franco first took restrictive measures in 1954, following a visit to Gibraltar by Queen Elizabeth that Madrid thought provocative. No more permits were issued to allow Spanish workers to cross over to work in British territory, and tourists were no longer allowed to leave Spain directly through Gibraltar. The issue was placed before the United Nations in 1963, which subsequently urged bilateral negotiations to restore Spanish sovereignty. Further restrictions were imposed by Spain two years later that eventually had the effect of cutting Gibraltars commerce by 40 percent. In October 1965 the regime announced a special building program for the Campo de Gibraltar, the Spanish territory around the enclave, to raise its living standards and present a more attractive alternative.

Castiella met with the British foreign minister in London to begin bilat-eral negotiations on May 18, 1966. Spain proposed cancellation of article 10 of the Treaty of Utrecht, thus restoring Gibraltar to Spain, and simultaneously offered to guarantee Britain the use of Gibraltar as a military base well into the future, along with special “personal status’ for the population of the district to be guaranteed by the United Nations. Britain pro- posed instead to allow a Spanish commissioner to reside in Gibraltar, to provide Spain with its own military facilities there, and to suppress all contraband activities (another perennial Spanish complaint). Following this impasse, the Spanish government denied permission for all over- flights to Gibraltar and rejected a request to submit the dispute to the International Court of Justice. The United Nations General Assembly, where Spanish diplomacy had courted Third World representatives, voted repeatedly to urge Britain to withdraw from Gibraltar, but it also re- quested Spain to prepare to decolonize its remaining Moroccan enclave of Ifni and the Spanish Sahara. Britain countered with a plebiscite on Sep- tember 10, 1967, in which the population of Gibraltar voted with virtual unanimity to remain under British rule. Two United Nations resolutions in 1967 and 1968 nonetheless condemned the British position and on De- cember 18, 1968 demanded termination of “the colonial situation in Gbraltar not later than October 1, 1969.” During 1969 the Spanish govern- ment proceeded to isolate Gibraltar as much as possible. As the deadline neared, the frontier was closed and telephone communications, ferry service, and the fresh water supply all cut off. Despite the pressure placed on Gibraltars economy, which had to be subsidized by Britain, no progress was made toward resolution of the dispute and no further initiatives were forthcoming after 1969. Franco rejected all suggestions inside his government for more extreme measures, recognizing that Spain was in no position to force the issue to its final conclusion and that it could be settled only by British withdrawal and not by Spanish seizure, a withdrawal that he realized would not be likely until after his own death."

The Problem of Spanish Guinea

"A Law of Provincialization in 1959 followed the example of Salazar's Portugal in giving the colonial population equal rights with Spanish citizens and providing for their nominal representation in the Cortes."

"Castiella emphasized the impossibility of Spain and Portugal holding out where Britain and France had already withdrawn. The Spanish regime would do what it could to maintain the stability of the Salazar regime at home...It prudently dissociated itself from a policy of diehard colonialism in Africa. "

"The limited Spanish presence that remained was deeply resented by the sinister new president, a former functionary of the Spanish administration once known as Francisco Macias. After rioting in March 1969 and an attempted coup against Macias by the foreign minister (following a trip to Madrid), United Nations assistance was invoked to evacuate the remaining Spanish citizens. Macias, who had reverted to his original name Nguema Masie Byoto, then imposed a harsh personal dictatorship—rhetorically decked in the garb of “scientific socialism”—-that stood out even among the bloody new African regimes of the 1970s for its genocidal propensities. As in many other areas, there was really no case for the hasty decolonization of Spanish Guinea except for the prevailing climate of political hysteria that made it difficult for Spain to remain. The final steps were accelerated by Madrid partly in the hope of building a stronger case for the devolution of Gibraltar, but the price that its new ruler exacted of this unfortunate region was among the most devastating in all the recent disasters of African independence."

The “Operación Príncipe”

"During the mid-1960s the regime weathered the rise in student, labor, and regionalist unrest with little loss in stability, and few Spaniards really expected its collapse or overthrow before the death of Franco."

"Some of Francos closest collaborators in the government, led by Carrero Blanco and López Rodó, nonetheless were uneasy about the future of Spanish institutions unless Franco took decisive action to give the system greater legitimacy and continuity by recognizing as successor a legitimate heir to the throne,"

"As the Caudillo put it, “For me the bad thing about the Traditionalists is not their doctrine, which is very good, but their determination to bring a foreign king to our country whom no one knows, who has always lived in France, and for whom the Spanish people feel nothing.” ° He himself denied the request of the Carlist Borbón-Parma branch to become Spanish citizens.

At no point did Don Juan, as direct legitimate heir to the Spanish throne, either in word or thought relinquish his own claim. During the preceding decade he had seemed to draw closer to the regime (for lack of any alternative), but by 1964 he realized that little had been accomplished to advance his candidacy. In February, Don Juan sent a personal memorandum to Franco urging him to take the step prepared for in the Law of Succession by institutionalizing the monarchy through the official recognition of himself, the legitimate heir, as Francos successor. This Franco categorically refused,’ and from that time relations between the two became increasingly hostile once more. During the next two years the Conde de Barcelona added prominent monarchist liberals to his personal council, in 1965 naming as his new political delegate in Spain the former regime politician and diplomat José Ma. de Areilza, who renounced his own past and invested his not inconsiderable talent in the cause of parliamentary monarchy. With the change in the censorship, Don Juans supporters became more outspoken. On July 21, 1966, the young monarchist writer Luis Ma. Anson published an article in ABC entitled “the Monarchy of Everyone,” which invoked “the European monarchy, the democratic monarchy, the popular monarchy” proclaimed by the Conde de Barcelona, bringing confiscation of the edition and temporary exile to the author.

By the early 1960s Carrero Blanco and his associates had firmly set their sights on Juan Carlos as the only appropriate heir to the throne and successor to Franco. "

"Juan Carlos had long been painfully aware of the narrow line that he must walk. He would later refer to it privately as many “years playing the fool in this country,” '* for he realized that he must avoid controversy to the point of appearing insipid and would only reach the throne through the monarchist succession created by Franco."

"Franco remained generally pleased with the prince, gratified by the relative simplicity of his life style (maintained on a slender budget) and his attentive manner. He made very little attempt to personally indoctrinate Juan Carlos, and was perhaps even willing to accept the possibility that the prince might make certain changes in the regime after his own death, apparently showing little alarm over an intelligence report which indicated that Juan Carlos had met with a small group of moderate liberals and leftists on May 27 and expressed a preference for a two-party electoral system under a restored monarchy.'*

"In June 1968 Juan Carlos reached thirty years of age, the age required by the Law of Succession to accede to the throne. That summer he was even being quoted in the international press as having let the diplomatic corps know that he was willing to accept power directly from Franco and bypass his father in the line of succession.''® The Conde de Barcelona himself doubted that Franco would ever name a successor in his lifetime, and later in the fall wrote to his son telling him that he had fulfilled his responsibilities well in Spain but must hold firm to dynastic principles and the proper chain of succession.'” On his part Juan Carlos, being briefed regularly by several cabinet members, believed that Franco would name him as his successor in a year or so.

By the autumn of 1968 Juan Carlos had begun to act with greater assurance, and his father may indeed have feared that Franco had succeeded in winning him over. In fact, Juan Carlos, behind his manner of winsome naiveté, had become a master of telling each person more or less what that person wanted to hear. Yet in an interview published in the French Point de Vue on November 22, 1968, he was quoted as stating categorically that he would never reign as long as his father lived. "

"Juan Carlos adopted a different tone in an interview with the official news agency EFE on January 7, 1969, when he declared himself ready to make “sacrifices” and “to respect the laws and institutions of my country’ —with respect to Francos Fundamental Laws—-in a very special way.” These remarks were carried in all the media'” and pleased Franco greatly. When he next met with Juan Carlos on January 15, the increasingly decrepit Caudillo gave him to understand that he intended to name him as successor before the end of the year. According to one version, Franco urged him, “Be perfectly calm, Highness. Dont let yourself be influenced by anything else. Everything is prepared.” Juan Carlos is said to have responded, “Dont worry, mi General. I have already learned a great deal of your galleguismo [slyness],” and after both laughed, Franco added,“ Your Highness does it very well.”**"

"On July 21, 1969, Franco finally presented the designation of Juan Carlos to the Council of the Realm and one day later to the Cortes. A special ruling arranged by Herrero Tejedor, attorney general (fiscal) of the Supreme Court, provided that the vote of ratification would be public so as to minimize opposition. The Cortes registered its approval by a vote of 491 to 19, with 9 abstentions, as a handful of die-hard Falangists and hardcore “Regentialists” held out to the end. On the following day, July 23, Juan Carlos officially swore “loyalty to His Excellency the Chief of State and fidelity to the Principles of the Movement and the Fundamental Laws of the Kingdom.” ” It seemed then that the long struggle for the instauration of a corporative and authoritarian monarchy, begun by Acción Espanola in 1932,'”’ was about to reach fruition."