Chapter 19: The Desarrollo

"The last twenty-five years of the Franco regime, from 1950 to 1975, were the time of the greatest sustained economic development and general improvement in living standards in all Spanish history. In one sense this was not so remarkable, because it coincided with the greatest period of sustained prosperity and development in all world history as well. Nonetheless, the proportionate rise in living standards and general productivity and well-being was greater than in other right-authoritarian regimes such as that of Portugal or those in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, and it was also greater than in the totalitarian socialist regimes in eastern Europe, Asia, or Cuba. Only Japan made greater proportionate progress than Spain during this period.

If Franco were to be resurrected and questioned about this, he would doubtless reply that such had been his plan all along. Certainly from the very beginning Franco and other spokesmen emphasized their determination to develop Spains economy and achieve a higher level of well-being, yet the policies and institutions under which the desarrollo was consummated were quite different from those on which the regime had originally embarked in the 1940s. Moreover, the reestablishment of Spanish influence in the world that was to accompany this never really occurred, while the remarkable cultural and religious counterrevolution carried out in Spain during the late 1930s and 1940s was totally undermined by the social, cultural, and economic changes wrought by development, as, in the long run, were,the basic institutions and values of the regime itself."

The Last Phase of Autarchy

"Though he considered economics of prime importance, Franco did not believe that economics required autonomy or needed to respond to market forces. Like most twentieth-century dictators, he continued to believe in the primacy of politics and that state power was capable of bending economics to its will.

The goal of force-drafting the economy with annual investment rates of 15 percent or more per year was largely achieved during the 1950s. Investment had begun to rise in 1948. It provided increasing support for electrical development and certain key industries by 1950, the commercial structure by 1951, the banking system by 1952, and public works by 1953. This policy continued to offer major tax advantages and even guar- anteed profits to favored firms, requiring the consumption of domestically produced goods as much as possible irrespective of price. Imports continued to be restricted, foreign exchange controlled, foreign trade regulated by the state, and direct intervention practiced through incentives and licensing for both exports and imports, together with the major investments of the Instituto Nacional de Industria (INI). Whereas the INI pushed fuels, fertilizers, and electric power during the 1940s, in the fifties it emphasized metallurgy and automobiles through large new enterprises such as ENSIDESA (Asturias) and SEAT (Barcelona). It was empowered to borrow large amounts of money from the Bank of Spain at only three-quarters of one percent interest, and savings institutions were required to place half their investment funds in INI stock.”"

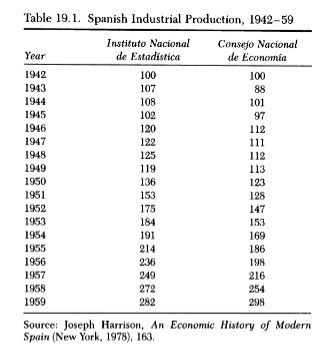

"In seven years industrial production doubled, and since agriculture failed to make equivalent gains, its share of total national production dropped from 40 percent in 1951 to 25 percent in 1957."

"Nevertheless this was growth from a shallow and uneven base. For years the system suffered from major bottlenecks, especially in the poorly developed road and transport system. Electrical output expanded rapidly, but demand grew even faster. Consumption remained low because of limited productivity and low wages (and the absence of special demand from a military-industrial complex). Moreover, the quality of many goods produced under state protection for a captive home market was inferior.

Insulation from international trade limited the market and the scale of production as well as the import of necessary goods and technology. Al- ready by the mid-1950s a significant proportion of plants and tools were thoroughly antiquated, while an increasingly sophisticated industry would demand more complex and expensive capital goods from abroad which could not yet be produced at home."

"Manuel Araburua encouraged more foreign trade, reducing the number of variable exchange rates from 34 to 6, and managed to close the autonomous accounts of some agencies while reducing others, all in the effort to achieve greater coherence. The rationing of basic necessities ended early in 1952, and tourism began to expand. Imports increased rapidly, doubling during the 1950s, in part simply be- cause of the accelerating purchase of food and other items of consumption to fuel a rising standard of living. Yet little was done to promote exports, which had registered a 15 percent increase between 1947 and 1948 and then another 10 percent in 1950 but largely stagnated in the decade that followed. The basic system of controls and restrictions remained, along with all the malpractices and distortions to which it gave rise.

American aid provided an important stimulus between 1953 and 1956, but further difficulties emerged. Continuing high inflation was due above all to the constant public deficits from 1954 on that were created in considerable measure by large state investments in the autarchist industrial program. Comparatively minor in 1954 and 1955, the deficit became severe by 1956. The demagogic across-the-board wage increases engineered by Girón were designed to boost consumption and thus encourage domestic production, but above all they accelerated inflation. The government printed more and more money but was tardy in stimulating agriculture, whose low output required growing purchases of food from abroad. "

The Stabilization Plan of 1959

"The economic ministers of the new government of 1957 were determined to confront these problems but had no coherent theoretical model or integrated general policy. When inflation or deficits climbed, the tendency within the regime had always been to blame poor administration or lack of government control rather than a fundamentally mistaken policy. "

"A series of piecemeal economic reforms were undertaken during 1957— 58, designed to help balance the budget and to introduce sounder monetary and exchange policies. In a major breakthrough, Ullastres unified the multiple foreign exchange rates but did not undertake a major devaluation or find the means to remove the numerous restrictions on commerce and investment. Navarro Rubio, the finance minister, tried to stem inflation by raising the rediscount rate of the Bank of Spain and limiting the amounts discounted.

Franco and Carrero Blanco were not anticipating any major change of economic policy but rather some adjustment and tightening of the existing system. Near the end of 1957 Carrero Blanco circulated a new proposal through the offices of the top economic administrators for “a coordinated plan to increase national production.” Rather than reform, this recommended an intensification of autarchy, insisting that a massive, almost Stalinesque mobilization of national resources would be the surest path to economic strength. It meant continued avoidance of the international market or the need to export, and the solution of the balance of payments problem by drastic reduction of imports. “We categorically reject, as unjust and egotistical, the easy argument of some that Spain is a poor country... .” The goal should be “not to have to import more than vital elements of production.”” This was of course not so much an economic proposal as a doctrinal projection, and there is no indication that it had any effect on the top economic administrators.

It flew directly in the face of the powerful new trend toward economic cooperation in western Europe, and such was its intention. Treaties to establish the European Economic Community (the Common Market) had just been ratified by six west European governments. The EEC officially came into existence at the beginning of 1958 and was a dynamic success from the start. The achievements of west European economic integration were already apparent to most Spanish administrators, and the development of the Common Market almost immediately exerted strong influence on many of them, who were soon convinced that the road to Spains future prosperity could not lie apart from the rapid economic growth of the western economy as a whole. The position of Franco and Carrero Blanco became the minority view even among the top economic administrators of the regime.

Somewhat slowly, Navarro Rubio, Ullastres, and López Rodó began to sketch the partial outline of a new program of economic liberalization and stabilization, while the inflation-fueled strike wave beginning in the spring of 1958 added further pressure. Navarro Rubio distributed a questionnaire to the directors of the states leading economic agencies to elicit their response to a possible liberalization of the autarchic system in the interest of international economic cooperation. Most were supportive, led by the administrators of the Syndical Organization, who now encouraged economic integration with Europe (with the hope that stronger sustained economic development might give them more influence in the Movement and the regime).* Administrators of the Bank of Spain were"

"the next change was the Ley de Convenios Colectivos (Law of Collective Bargaining) that appeared in April. It introduced the novel principle of local collective bargaining between employers and labor under the framework of the Syndical Organization, if this were found preferable to the industry-wide norms that the Ministry of Labor had supervised heretofore. Though the ministry retained the power to dictate agreements when collective bargaining broke down, the law provided much greater individual and local initiative, allowing more active and efficient firms and syndical units to determine their own norms and to that extent giving the Syndical Organization a more direct role than before. Collective bargaining nonetheless got off to a slow start, because of the deflationary, recessionist conditions of 1959-60. Only one local collective bargaining agreement was signed in 1958, followed by 179 in 1959, the number rising to 412 by 1962."

As first steps in a new direction, in 1958 the regime entered the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), the Export-Import Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. The new Spanish budget provided special incentives to export and for the first time timidly widened the door to foreign investment." Late in the year the principal west European countries made their currencies freely convertible, increasing pressure on Spain to do likewise. The pathology of Spain's situation was underscored in December 1958 when police caught two Swiss banking agents in a massive evasión de pesetas (illegal smuggling of Spanish currency abroad). The agents were also caught with a list of 1,363 wealthy or prominent figures—including of course various officials high in the regime—whose secret Swiss bank accounts they serviced.”

A crisis was reached in mid-1959 after four years of severe balance of payments deficits and inflation. In May the OEEC issued a report on Spain, pointing the way to major reform. By July the Instituto Español de Moneda Extranjera (Spains foreign currency exchange) was very close to having to declare suspension of payments, while the stock market had gone into decline after the restrictive measures of the preceding year. With the government facing bankruptcy, the economic ministers concluded that a fundamental change of direction could no longer be delayed."

"when Navarro Rubio presented to Franco the outline of a new plan of stabilization and liberalization, Franco “did not at first have the slightest confidence in it,” '* discerning merely the abandonment of much of the regime's program in favor of unregulated interests. Moreover, he had always viewed greater economic liberalism as inherently tied to political and cultural liberalism, and reliance on foreign investment and international commerce as inevitably opening the door to subversive foreign political and religious influences. "

"a new decree law was issued for a “plan de estabilización interna y externa de la economía.” Its goal was retrenchment, deflation, and above all a liberalization that would open the economy to the international market. The peseta was devalued from 42 to 60 to the dollar, and by the end of the year, eighteen government control agencies had been abolished and a wide variety of items freed from regulation in both domestic production and foreign trade. Restrictions were placed on credit, and the Bank of Spains rediscount rate was again raised, this time from 5 to 6.25 percent. Import licensing was abolished for 180 commodities deemed essential imports, representing about 50 percent of all imported goods, while controls were retained on less important items to protect foreign exchange. Internal investment was largely freed from government restriction, more careful guidelines were set for state investment, and new regulations encouraged foreign investment for up to 50 percent of the capital investment in any individual enterprise. The previous limit had been 25 percent, and even that had been hedged with serious restrictions and limited to certain kinds of firms. The new regulations, which greatly simplified and expedited procedures, applied to all firms and allowed foreign investors to repatriate freely annual dividends of up to 6 percent. This was obviously not a program of full free-market economics, for many restraints remained, but it did create a significant opening to market forces. Much though not all of the “Falangist” system of semiautarchist economic nationalism had been demolished at one stroke.

The Stabilization Plan gave a jolt to the man in the street, temporarily increasing unemployment and bringing a slight drop in real income for about a year, but its main goals were soon achieved. The danger of sus- pension of payments was averted, and within five months, by the close of 1959, Spain’s foreign exchange account showed a $100-million surplus. New foreign investment rose from $12 million under the old restrictions in 1958 to $82.6 million in 1960, while between 1958 and 1960 the annual number of tourists doubled from three to six million and thenceforth continued to rise rapidly.”"

"Further reforms followed. A new tariff in 1960 systematized the changes in levels of protection. Two years later the Bank of Spain was nationalized and new antimonopoly regulations imposed on industry and commerce to encourage competition. A modest tax reform was then carried out in 1964 that simplified the tax system and made it slightly more progressive."

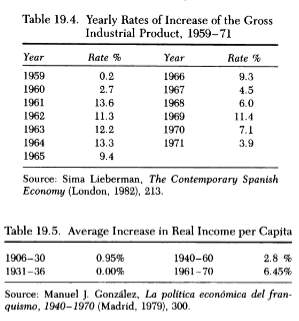

"The liberalization initiated the greatest cycle of industrialization and prosperity that Spain had ever known. Proportionately the most successful years were 1961 to 1964, the years before the plan was in effect, for they registered a real growth in GNP of 8.7 percent a year, on a higher base than in the fifties. During those years inflation was held to an average rate of less than 5 percent annually.” Moreover, most aspects of national economic policy had been brought into the open and were henceforth subject to varying degrees of criticism, creating something of a national economic debate during the last fifteen years of the regime, in sharp contrast to the official dictates and closed-door dealing of its first two decades.

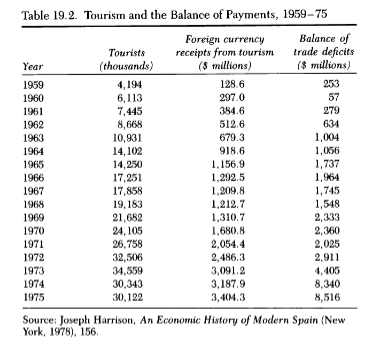

Foreign investment and export growth were vital to this program. The former came by means of massive and growing tourist expenditures and by major direct investment in industrial enterprises. Spains tourist industry blossomed into one of the most efficient in the world, drawing 21 million annual visitors by the close of the decade and still increasing.” At one point it accounted for at least 9 percent of the gross national product, centered on Madrid and on the eastern and southern coasts. Dour, neotraditionalist Spain was rapidly transformed into a “good-time” vacationland, with cultural consequences to which the native population could not be immune. Spanish expertise even made it possible to mount small technical assistance programs to a few Latin American countries attempting to develop their own tourist industries.” Export growth itself always remained far from sufficient to balance the trade deficit, resulting from increasingly large imports of food and capital goods, but as table 19.2 indicates, receipts from tourism were responsible for covering most of the remaining gap during the next fifteen years.

Second only to the receipts from tourism was the total of direct foreign investment, which from 1960 to 1974 came to more than $7,600,000,000. Of this, nearly five billion was invested in properties, over two billion in direct commercial and industrial investment, and the remainder in stock market purchases. More than a billion dollars in additional funding was made available from foreign sources through various loan and credit devices. Of the direct investment, more than 40 percent came from the United States, nearly 17 percent from Switzerland (of whatever origin), slightly more than 10 percent each from Germany and Britain, more than 5 percent from France, and almost 5 percent from the two Low Countries combined. Foreign investment was heaviest in automobile manufacturing (where more than 50 percent of industrial capital was of foreign origin by 1970) and in electronics and the chemical industry (where foreign capital amounted to 42 and 37 percent of the totals, respectively, by the end of 1973). Altogether, before the close of the regime, 12.4 percent of all the capital invested in the 500 largest industrial enterprises was of foreign origin.” Some industries such as textiles, the oldest in Spain, received very little foreign investment. That investment was disproportionately concentrated in the new industries of the central area around Madrid, which received nearly 36 percent of the total, and in Catalonia, which got 26 percent."

"The strongest opposition came from certain sectors of the Movement and within the state economic structure from Suanzes and the INI. Suanzes himself resigned before the close of 1963, and although one of the oldest friends of the Caudillo, broke off relations with him.” The new policies tended to limit investment in the INI, yet its holdings continued to grow. By the time of Francos death they were responsible for or involved in 15 percent of all exports, 76 percent of all shipbuilding, 64 percent of heavy trucks built, 50 percent of the coal mined, 67 percent of the aluminum, 58 percent of the iron, and 45 percent of the steel, 46 percent of the automobiles produced, 37 percent of the petroleum refined, and 23 percent of the electrical energy produced.” Yet the INI was not a truly powerful autonomous institution, for it lacked independence and was poorly coordinated. It increasingly came to serve as a state safety net for inefficient and failing private enterprises, and in later years was required to take over and compensate for the losses of leading shipbuilding and coal-mining companies. The direction and central administration of the INI was not in itself inefficient, but it maintained a total of 4,000 executive positions throughout Spain, half of which were political sinecures. The lack of rationalization and coordination among its enterprises as well as the stagnation in some of them became clearer with each passing year. After 1970 an entire generation of reorganization and reform was initiated, as more and more of the older enterprises operated at a loss.”"

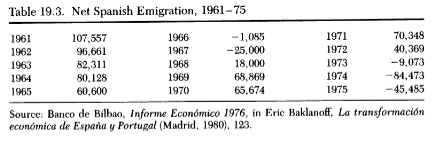

"The new policies were generally supported by the Syndical Organization but were at first unpopular with the workers, since wages were nearly frozen between 1957 and 1961. The temporary decline in real income during the initial main phase of stabilization in 1960 stimulated what soon became a wave of Spanish surplus labor migration to the labor- short industries and service jobs of France, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland, as western Europe absorbed nearly a million Spanish workers during the next decade.* This supplemented the great expansion of employment in Spain that followed, eventually making possible almost complete elimination ofurban unemployment and much of rural underemployment, while the remittances of foreign workers provided further sources of international exchange."

"Results from the First Plan of Development of 1963 were nonetheless never quite according to plan, despite impressive growth figures. A high rate of internal investment was sustained for several years, with nearly 23 percent of the GNP invested in 1965 thanks to the easy terms of credit for productive enterprises. Yet industry itself was financing only 27 percent of its own investment directly through reinvested savings and profits. In 1965 the inflation rate shot up to 14 percent, leading to new deflationary restrictions not foreseen in the plan. The second half of the decade was a time of “stop-and-go” in Spanish industrial policy, with minicrises in 1966-67 and to a lesser degree in 1970-71. The main neoliberal phase could be said to have ended in 1966. Spain still had two and a half times the level of tariff protection of the average non-Communist industrialized country (and nearly twice that of Japan). A new decree of 1967 limited the installation, expansion, or transfer of industrial enterprises once more. Further policy reform was needed at that point, but as Francos health and energy declined, leadership became less assertive and no one could or would take responsibility for changes. Following a major increase in the minimum wage in 1966, a deflationary program the following year further devalued the peseta by 17 percent, cut the national budget, and temporarily froze prices and wages. "

"Expansion temporarily accelerated once more early in the seventies, so that Spain’s average annual growth rate for the fifteen years 1960 to 1975 was 7.2 percent—certainly the highest figure in Europe and second in the entire world only to Japan. Industrial productivity per worker was still less than 40 percent that of Germany and less than 45 percent that of France in 1970, but in 1969 Spain achieved the rank of twelfth largest industrial power in the world, and later climbed to eleventh. In 1971 it was momentarily the world's fourth largest shipbuilder.*"

"The regime’s leaders recognized that severe regional economic im- balance was a fundamental feature of Spanish underdevelopment which must be overcome. Under the development plan, special “poles of devel- opment” were targeted for six underdeveloped areas: Vigo in the north- west, Burgos, Valladolid, and Zaragoza in the north, and Huelva and Seville in the south.* This strategy was not generally successful, for mas- sive investments would have been required to overcome the lack of in- frastructure and sociocultural prerequisites in the more backward agrarian provinces. As it was, part of the state investment was poorly or improperly employed. Huelva received vastly disproportionate funding and devel- oped a huge chemicals complex but remained an industrial island in a backward agrarian province. The only other two “poles” to approximate their goals were Vigo and Valladolid, though Zaragoza profited considerably from increased private investment.”"

"Spain became a country of larger and larger cities; by 1970 40 percent—and by the time of Francos death in 1975 50 percent—of its population lived in cities of 100,000 or more. "

"Rapid development reduced somewhat the concentration of banking sources that had developed in the 1940s, so that by 1967 the five largest banks controlled only 56 percent of the country's private banking resources and the eleven largest about 75 percent, amounting to decreases of 12 and 8 percent respectively over the preceding decade. The financial power of Spanish banks was not greatly diminished, however, and the state in some respects did little to regulate them, allowing them to maintain the highest bank margins in western Europe. Though 30 percent of all deposits were nominally required to be invested in state-approved projects, Spanish industry became heavily dependent on private banks, which controlled 40 percent of all industry by the time of Francos death."

Agriculture

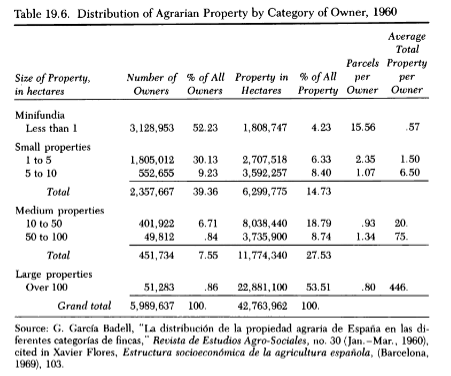

"Minifundia—tiny, often widely separated uneconomical cultivation plots—were as much a problem as latifundia, and the state sponsored a Servicio Nacional de Concentración Parcelaria (founded in December 1952) to concentrate small plots into economically viable units. It was empowered to reorganize whenever either 60 percent of the landowners or those owning 60 percent of the land in a district requested concentration. Ultimately about 4 million hectares, or about 10 percent of the farmland of Spain, was so reconcentrated, but even in the last years of the regime millions of uneconomic minifundia remained.* Thus one study in 1965 found that 48 percent of all landowners, the true minifundists, had a cash income even lower than that of rural day laborers.

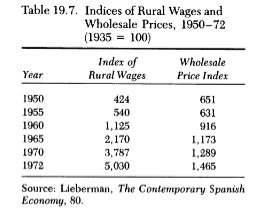

Many agrarian producers increased their incomes significantly in the black market of the forties, and the elimination of rationing in 1952, which destroyed the black market, temporarily depressed their condition. The only benefits for the lower strata of agrarian society provided by the regimes own regulations during the early years were security of tenure for renters at relatively fixed rates and a kind of minimum wage for laborers. In general, the income of laborers and some minifundists declined during the 1940s, like that of urban workers and much of the middle classes, but the wages of farm laborers began to rise rapidly after 1950 and spurted upward during the later years of that decade.

The government enacted legislation for the eviction of landlords who did not properly use their land or tend to larger estates, and it provided for the collectivization of large units under carefully delimited conditions,"

"but such powers were rarely invoked. Much more successful were the large-scale efforts to promote the reforestation of large tracts of barren hillsides which by the 1960s had considerably increased the amount of tree cover in the peninsula. Irrigation facilities were also greatly expanded, sometimes in connection with hydroelectric projects. One major rural regional project, the Plan Badajoz, was implemented in Extremadura during the 1950s. It attempted to combine new irrigation facilities, electrification, resettlement of landless families, reforestation, and the development of secondary agrarian industries, * but it was not a complete program of regional development and met only limited success. In fact, the irrigation programs undertaken by the regime during its first two decades tended primarily to benefit larger landowners, and though they did expand production, at first had limited effect on the structural and social problems of the countryside.

Agrarian policy became more active during the 1950s, and the following decade of the sixties was in some respects even more decisive for agricul- ture than for industry. Grain production was stimulated by a new pricing policy in the fifties, and after 1958 the state introduced an increasing array of incentives, loans, and credits to stimulate productivity and modernization. New opportunities for higher wages in domestic industry or abroad in western Europe provoked a mass exodus of underemployed agrarianlaborers and minifundists. The shrinking labor supply, together with the general prosperity, further stimulated the dramatic increase in rural wages. Bountiful credits and loans helped to dramatically expand mechanization and the use of fertilizers, the number of tractors spurting from one for every 228 hectares in 1962 to one for every 45 hectares by 1970and the number of motor cultivators increasing with equal or greater rapidity."

"Agricultures percentage of the total Spanish GNP shrank from 24 in 1960 to only 13 in 1970, representing proportionately less than in Italy, Greece, or Portugal. The active agrarian population diminished from 4.9 million in 1960 to 3.7 million in 1970, and by 1970 represented only 22 percent of Spains active population. Even in some of the prosperous agrarian areas of the northeast, the agrarian population declined because of the inherent unattractiveness of a rural lifestyle in an urban, hedonistic, consumer-oriented society. Prosperous family farms transferred in one form or another from generation to generation over centuries disappeared in the Basque provinces and Catalonia not because they were economically unprofitable but simply because agriculture was disagreeable."

Social and Cultural Transformation

"By the time of Francos death, 40 percent of the labor force was employed in services (reflecting the massive growth of tourism), 38 percent in industry, and only 22 percent in agriculture, the primary sector. This pace of development reoriented social psychology, which became attuned to the common consumerist and hedonist culture of the western world in the second half of the twentieth century."

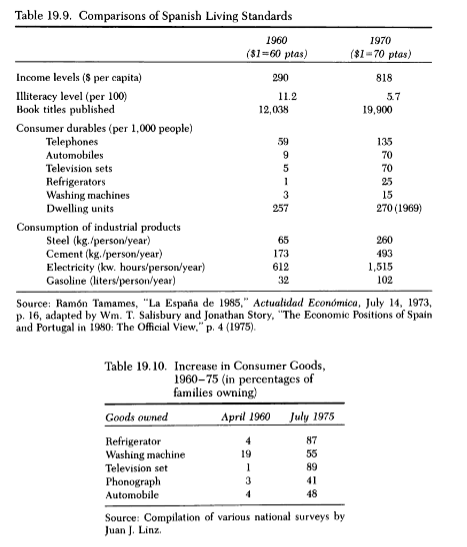

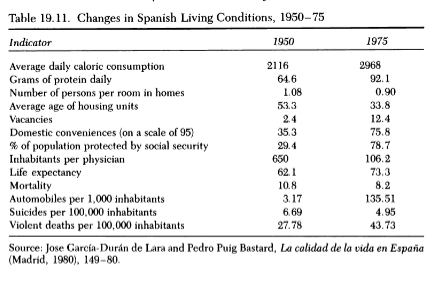

"In the 1940s the Ministry of Labor initiated a modest social security system. Regular contributions were paid by both workers and employers. At first the system was restricted basically to industrial labor and the service sector. In a comparatively youthful population, retirees were relatively few, and payments caused little strain, despite a low level of contributions. Social security was greatly expanded in 1964 to include the agricultural population.” This added nearly two million names to the rolls at the same modest rate of contribution, insufficient to fund the system inthe long run. Small shopkeepers and others who were self-employed were included in 1971 on much the same terms, but by that point retirements were increasing and the Spanish system began to run a deficit for the first time. Reforms of 1972 increased contributions somewhat, but those workers who had not yet been covered were then included in the system. Deficits became severe by 1974, and there were many complaints of fraudulent claims and too-lenient terms for disability. (Eventually some provinces would contain more nominally disabled workers than regular retirees.) As in other systems, the tendency was to pay much the same benefits to everyone, regardless of amount or number of years of contribution. These would soon become standard problems in other western industrial countries. The Spanish system was more poorly designed than some, but a welfare state had been created, accompanied by very rigid job security enforced by the syndical system.

The growth in educational facilities was proportionately even greater in some respects than that of industry. By 1970 the Spanish state for the first time was spending more on education than on the armed forces. The last full year of Francos life, 1974, marked the first year in history in which elementary school was available to almost every Spanish child (with the exception of those in a few isolated mountain villages). The quality was uneven and often left a good deal to be desired, but the schools were there and available to nearly all. By that time, with the opening of a second chain of universities, the number of Spanish universities had nearly doubled to twenty-two. The volume of university students increased rapidly during the 1960s, then skyrocketed between 1970 and 1974 with a breathtaking 500 percent increase. This was a reflection, despite the radical nature of student politics, of the new embourgeoisement of Spanish life and of the great transformation of status, income, and aspirations."

The Limits of Development

"By the end of 1973 annual per capita income passed the coveted threshold of $2,000 (which López Rodó had earlier declared would be sufficient to prepare Spain for democracy). In real dollars, this figure was equivalent to that of Japan only four years earlier. At that point Spain ranked ahead of Ireland ($2,034) and far ahead of Greece ($1,589) and Portugal ($1,158),% not to speak of Latin American or Third World comparisons."

"Economic policy was nonetheless subject to an unprecedented barrage of criticism from the mid-1960s on. The new economic leadership itself brought the discussion of government policies out into the open, while the censorship reform that took place in 1966 made it possible in most cases to criticize strictly social and economic problems without penalty, as long as the politics and legitimacy of the government were not called into question. Critics held that Spain had largely failed to overcome major structural defects, that the development was dependent on foreign capital and the international boom of the sixties. "

"The large national banks did exert major influence but no more than in Belgium, and probably only slightly more than in France and West Germany. "

"The system was never fully opened to the market, for a broad variety of price and exchange controls remained for specified activities, as well as a continuing fairly high degree of industrial regulation, trade protection, and artificial agricultural supports. The corruption that had bee a major byproduct of autarchy may have diminished, but it nevertheless continued to be widespread. In most industries, the optimal scale of enterprise was not fully attained, making it difficult to achieve complete rationalization, cost efficiency, and the most sophisticated application of technology. Despite the general transformation of agriculture, food production was increasingly specialized and was generally inadequate for Spanish needs, requiring perpetual large-scale imports. Though inflation was reduced in the 1960s, it was never eliminated and in later years was greatly stimulated by easy credit and other official policies. The Syndical Organization both restricted and overprotected workers, official regulations making it difficult to fire redundant employees for sloth, minor misdemeanors, inefficiency, or sheer redundancy, and this promoted featherbedding and discouraged more rapid advances in productivity. Nevertheless, the rapid growth in industrial employment (contrasted with the enormous shrinkage of the agricultural population) was never sufficient to provide full employment without major emigration of workers. When emigration began to decline, starting in 1973-74, the result was increasing unemployment. The notable efforts to expand further the scale and coverage of state welfare in the last years of the regime increased industrial costs and fueled inflation. Industrial investment remained dependent on cheap credit provided by state policy and the banking system, and to a lesser degree on foreign capital—factors that would be much more difficult to sustain after 1973. Several key industries, such as Basque metallurgy, began to age, failing to renovate their capital investment and technology. The INI had become a bloated white elephant by the end of the regime, for the attempted restructuring of the early 1970s turned out to be inadequate to convert many of the subsidized industries into going concerns. Though this was often the case with nationalized or state-supported industries around the world, such knowledge provided scant comfort.

Despite the statist economic pretensions of the regime during its first two decades, by its close the Spanish government's domination of economic resources was proportionately the least of any country in Europe. The limited reforms of 1957 and 1964 did not greatly alter the fact that the fiscal system remained highly regressive and ridden with loopholes. Even when social security and other welfare categories were added, the state budget in 1973 amounted to only about 21 percent of GNP. Regular taxes were equivalent to only 13.5 percent of GNP, compared with 15.6 percent in Japan and 22.5 percent in France, to contrast Spain with the two most lightly taxed of the major industrial countries. Approximately 44 percent of all Spanish taxes were indirect, a figure exceeded only marginally by France at 45 percent."

"The Spanish economy was protected from the immediate effects of the international oil crisis of 1973 by government policy, which kept petroleum prices well below the European average. Spain then depended on petroleum for 69 percent of its energy, and scarcely 2 percent of that waproduced domestically. The overriding goal was to sustain the general growth rate, which for 1974 was 5.4, slightly below target yet still a worthy achievement.” Yet the oil price rise greatly burdened the foreign ex- change account and was a prime factor in increasing the inflation rate to 18 percent in 1974, beginning the steep new Spanish inflation that would reach even higher rates during the remainder of the decade.

By the time of Franco's death, the Spanish economy was faced with a major international recession, a sharp decline in foreign investment, and a drastic falloff in the growth rate. Some of the major industries such as metallurgy and shipbuilding proved unable to compete in the new environment, and the unemployment rate soared.

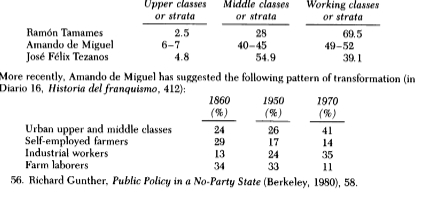

Despite the broad transformation of Spanish social structure, severe economic inequalities remained between advanced and lagging regions and between the rich and the poor. Though much of the population was becoming more or less middle class, in 1970 the wealthiest 1.23 percent had a larger share of the total national income (22.39 percent) than did the lower 52.2 percent of the population (who had only 21.62 percent of the national income).* By the time of Franco's death, “the richest ten percent were nearly twice as rich as their opposite numbers in the United Kingdom.’ "

The Consequences of Development

"That the regime leaders had not counted on was the profound social and cultural changes that accompanied development. Full employment and steady, unprecedented increases in income for nearly all social sectors created the first experience in mass consumerism in the life of Spain. The possibility of a new society oriented toward materialism and hedonism, never before remotely within reach of the bulk of the population, quickly became a reality. Rural and small-town society—in the north the socio- geographic backbone of the Movement during the Civil War—was progressively uprooted. Despite continuation of a steadily attenuated state censorship, foreign cultural influences entered Spain on a scale previously unimaginable. Mass tourism, combined with the movement of hundreds of thousands of Spaniards abroad and then home again, exposed much of society to styles and examples widely at variance with traditional culture but often most seductively attractive. This was accompanied by mounting bombardment from the contemporary media and mass advertising. The transformation of the cultural environment was absolutely without parallel.

The first victim of this transformation was not the regime but its primary cultural support, the traditional religion. A highly urban, sophisticated, materialist, nominally educated, and hedonistic Spain, increasingly attuned to the secular and consumerist life of western Europe, simply ceased to be Catholic in the traditional manner...During the course of the 1960s, the regime found that it was less and less able to count on the Church, and by the end of that decade many of the clergy had become the primary public spokesmen for the opposition.

Though Franco was never seriously challenged as long as he lived, the surviving government administrators would find that by the time of his death, the kind of society and culture on which the regime had primarily been based had largely ceased to exist, and that would make it impossible for the regime to reproduce itself. Ultimately the economic and cultural achievements that took place under the regime, whether or not they were intended to develop as they did, deprived the regime of its reason for being."