Chapter 16: Social and Economic Policy in the 1940s

"There is no doubt that the program of autarchy was generally inefhcient.! Policy was relatively arbitrary and frequently improvised, and it varied considerably from one sector to another with little attempt at coordination. It intended to discourage the international market and exports in general while emphasizing import substitution industries. State controls determined nominal prices and wages in most categories, and state policy reinforced the existing structure of small enterprises by providing credit no matter how inefficient the firm. Thus the economies of scale required for optimal functioning usually could not be achieved, and when new plants were established in nonindustrialized areas—laudable from the viewpoint of overcoming regional imbalance—that also increased their cost. "

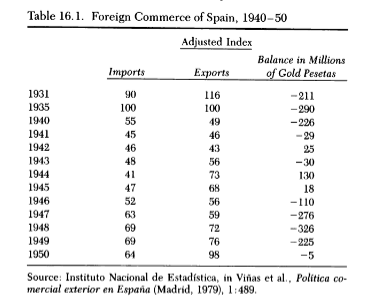

"Autarchy was most rigorous in foreign commerce and exchange.? As indicated in table 16.1, Spain regained her approximate pre-Civil War level of exports only in 1950, while financial stringency and a persistently negative balance kept vital imports below the norm of 1936.

By this time Franco had abandoned his extravagant notions about Spains national resources. He almost reversed the argument in an address to Asturian miners in May 1946, attributing Spains lower standard of living to her lack of colonies. “Nobody in the universe works for Spain,” the Caudillo declared. “Spaniards earn their bread by the sweat of their brow.”* Such an explanation was well suited to the pompous rhetoric of the period, for it arrogated to Spain a position of moral superiority, relatively poor but honorable and nonexploitative compared with the major powers.

State policy emphasized coal and steel production and hydroelectric expansion, areas that had registered major gains by the close of the 1940s."

"General industrial production surpassed the 1935 level by 2 percent in 1946. Textiles languished, even in 1948 reaching only 60 percent of the pre—Civil War figure. The chemical industry did not regain its 1935 level until 1950, but as early as 1940 coal output exceeded the prewar total by about 30 percent and by 1945 was more than 60 percent higher. The most spectacular growth was in electrical production, which by 1948 was nearly double that of a decade earlier even though drought still left intermittent shortages. By 1948 overall investment began to accelerate, and from that time industrial expansion was more general.* The first all-Spanish transport plane was produced in 1949.

Agriculture, the largest division of the economy, remained with textiles the most depressed, total production continuing well below averages for pre—Civil War years. A Ley de Intensificación de Cultivos was promulgated in 1940 to try to force landowners to bring more soil under cultivation, but state compulsion—not very rigorously enforced in Spain—had no more success than in the Soviet Union. In 1939, only 77 percent of the wheat-growing area cultivated before the war was under production, and this increased very slowly, finally reaching 90 percent ten years later.* The 1941 wheat harvest was only 2.4 million tons, whereas nearly 4 milliotons were needed. Weather conditions were intermittently very poor for much of the decade, the drought of 1944-45 resulting in the lowest cereal harvest of the century, worse even than the calamitous year 1904 (previously the poorest). Thus wheat production in 1945 was only 53 percent of the pre-Civil War average, and by 1946 food production had risen to only 79 percent of the 1929 level, falling back temporarily to 64 percent in 1948."

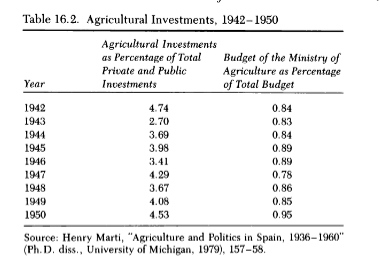

"Miguel Primo de Rivera, minister of agriculture from 1941 to 1945, had no qualifications whatever for the position, though his successor and fellow Falangist, Carlos Rein Segura, did hold a degree in agricultural engineering. The Spanish state simply paid little attention to the agricultural base of its economy in allocating production resources (see table 16.2). Throughout the decade of rationing and severe hardship it was thus necessary for a still primarily agricultural country to use much of its limited foreign ex- change to import basic foodstuffs. (Spain was not alone in this; it has been a common experience for underdeveloped twentieth-century economies. )

Not surprisingly, foodstuffs were the most important commodities on the widespread black market of the 1940s. The National Wheat Service was unable to fully control grain supplies, so that about one-third of all grain produced in the country during the forties ended up on the black market.” Since this was sold at much higher than government prices, it provided about 60 percent of the income of domestic grain producers. A law of September 30, 1940, provided for stiff fines and prison terms for buyers and sellers in the black market, and as mentioned earlier, the death penalty was soon afterward instituted for particularly serious crimes. During the first year of the new sanctions approximately 5,000 traffickers were sentenced to prison and more than 100 million pesetas in fines were levied,® but this had very little effect, because of the extreme shortages and, the maladministration and growing corruption of the system. Moreover, new regulations in 1941 and 1943 no longer required grain growers to deliver all their wheat to the National Wheat Service, thus in effect legalizing part of the market activity. Critics pointed out that the grain growers of the north had largely supported the Nationalist cause in the war, whereas the most severe hunger and food shortages were suffered by urban workers and poor southern peasants, who had been on the other side."

"Despite the reduction in the area of land cultivated, the agricultural labor population continued to grow, in part because of restrictions and unemployment in urban industry and in part because of natural demo- graphic increase. The rural labor force increased altogether from 4.1 million in 1932 to 4.8 million in 1940 and to 5.3 million in 1950* before it eventually began to decline. "

"By the end of the 1940s some areas began to register real improvement in expanding irrigation and providing other technical facilities to augment production. Investment in agriculture, which averaged less than 4 percent of all Spanish investment during the forties, suddenly doubled to 9.33 percent in 1952, and then increased further during the remainder of the fifties." Approximately half of total investment came from public funds. Thus after midcentury significant changes finally began to affect Spanish agriculture, beginning the transformation that would take place during the last twenty-five years of the regime."

"A major limitation on the regime's ability to prosecute more rapid autarchic development was its weak fiscal policy. Direct taxes had always been light in modern Spain, though excises weighed heavily on those of modest means. Within the system there was great resistance to changing this, for any policy of more progressive taxation smacked of socialism or collectivism, which Franco was determined to avoid. The government had absolutely no interest in redistributing income through taxation, and thus in 1948 only 14.76 percent of the measured national income of Spain was collected in state revenue, compared with approximately 21 percent in France and Italy and 33 in Britain.”

In this situation the big winners under the stringent Spanish economic conditions of the 1940s were the banks, particularly the big banks. The

five largest banks (Central, Español de Crédito, and Hispano-Americano in Madrid, and Bilbao and Vizcaya in Bilbao) expanded at what was probably an unprecedented rate, increasing their annual profits by about 700 percent. According to estimate, they dominated about 65 percent of the mobilized financial resources of Spain in 1950,’ an ironic commentary on the rejection of the original Falangist program of controlling the banks through nationalization of credit.

For Spain as a whole, the 1940s were a decade of prolonged hardship. Actual conditions varied somewhat from region to region, for the more advanced areas normally did better, and energetic civil governors sometimes managed to expand the food supplies for individual provinces. To some extent the black market created a new middle class and was actually necessary for survival; the civil governor of Valencia pointed out in 1947 that the daily food consumption guaranteed by rationing in his province amounted to only 953 calories.'"

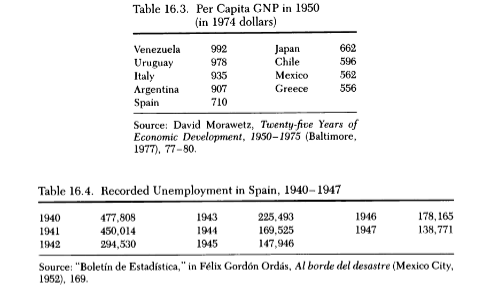

"By the end of the decade Spain stood near, though not at, the bottom of economic development in southern Europe, well behind the most prosperous countries of South America (a comparison that would change rather dramatically in later decades) (see table 16.3). Pre—Civil War per capita income was not regained until 1951. Compared with that of 1935, adjusted per capita income stood at 79 in 1940, rose to 87 in 1942, held at that approximate level during 1943-44, then sank to 71 in 1945 before beginning to rise again."

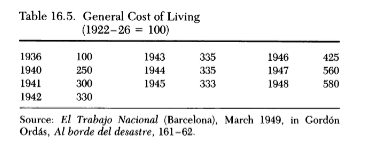

"The 1940s brought the worst inflation in Spanish history. This had largely been avoided in the Nationalist zone during the Civil War but had gotten completely out of control in Republican territory and in the post- war dislocation began to afflict the entire country in 1939-40. After prices had generally increased about 150 percent over the prewar level by the close of 1940, they were partially stabilized during 1942-45. But in 1946 they rose nearly a third, and almost as much in 1947 before tapering in 1948, when they stood at nearly six times the level of 1936. Moreover, the price increase was steepest in foodstuffs, which accounted for a higher proportion of expenditures among the lower classes. Nominal wages increased much less than prices, though some of the diflerence was made up by second jobs, black market activities, and the beginning of the social security system. It was not until 1952 that the general standard of living finally climbed above that of 1936.

The most impressive achievements of the 1940s took place in medical care and sanitation of the most fundamental kind. There was no possibility that a country at Spain’s level of development in those years could provide sophisticated, high-quality medical service for all, but quite a bit was accomplished in such basic areas as childbirth and infant care. Infant mortality, for example, declined from 109 per thousand live births in 1935 to 88 ten years later, and had been reduced by half—to 55—by 1955. The maternal death rate similarly declined from 2,196 for every 100,000 births in 1935 to 1,183 after a decade, and to less than half—465—by 1955.

The welfare system of the regime evolved in piecemeal fashion. The first provision for family subsidies to unusually large or needy families was announced on July 18, 1938, and by 1942 about 10 percent of the population was receiving supplementary income from it.?” A new state insurance program began with the Seguro de Vejez (Old Age Insurance) on September 1, 1939, though this was not extended to agricultural workers un- til February 1943, followed by the Seguro Obligatorio de Enfermedad (Compulsory Sickness Insurance) on December 14, 1942. Though the re- gime reversed nearly all the property transfers carried out by the Re- public and the revolution, its social policy was not simply reactionary, for it preserved or adapted much of the social legislation that preceded it, and in some respects extended it.'* One innovation was the new Ministry of Housing, eventually raised to cabinet rank in 1957, which financed con- struction of new housing for low income groups on a national scale for the first time in Spanish history. Though the construction of only about 13,000 units per year was subsidized during 1940 to 1944, the number increased to 20,000 in 1946, 30,000 in 1947, and more than 42,000 in 1950.** All this fell far short of the need, but it was the beginning of the franquista welfare state, a system that never convinced its original “class enemies ”— industrial workers and landless peasants—but one whose pro- vision of welfare accelerated significantly during following decades."

"Workers’ benefits and general social welfare were divided between the Syndical Organization and the Ministry of Labor, which further limited the former's influence. Whereas syndical organization was not completed for many years, general welfare benefits such as medical services were steadily developed by the labor ministry for the broader population and were not limited to syndicate members. "

"In general, the syndicates were able to dominate the workers but not to generate much in the way of real support. The influence of the syndical system was particularly weak in such areas as Barcelona, Vizcaya, and Asturias, where organized labor had previously been strongest. The civil governor of Barcelona from 1945 to 1947 would write a year later with surprising frankness: “That the working masses do not always find themselves represented in their syndicates is evident. Workers often do not recognize the moral authority of their own delegates, saying that they are the servants of boss so-and-so. Others say that political influence deter- mines that the leaders be persons who do not hold office to benefit the workers but to benefit other sectors or their own pocketbook.”? Some of the most imaginative syndical leaders hoped to coopt part of the opposition and were particularly interested in the clandestine CNT, which still had significant labor support in Barcelona and a few other regions, but efforts to negotiate some sort of pact with members of the CNT leadership during 1946-47 were unsuccessful.” Thus Francos cousin Salgado Araujo would write privately eight years later, “What is sad is the gulf between the mass of workers and the Syndical Organization, since the big shots are not popular leaders in contact with the workers, but superiors who exploit their positions. . . .* Whatever strength the Syndical Organization possessed was derived from its status as a state bureaucratic organization, not from direct worker support."