Chapter 11: The Repression

"From the very beginning, the political violence that attended the struggle in Spain attracted widespread publicity and revulsion, not be- cause it was more severe than in other revolutionary civil wars but simply because it was the first to be widely publicized, and took place in a west- ern country at that. On any reasonable comparative scale, political violence against civilians in Spain would have to be rated somewhere in the middle range among conflicts of this type. It was more severe than that of Hungary, rather less than that of Russia, and as indicated, about the same as that of the only example to be found in Protestant Scandinavia.

Political violence had already become a major factor in mutual polarization before the war began. All the left revolutionary groups made re- peated appeals to the legitimate use of revolutionary violence, as did the Falangists, and the rightist radicals differed only in the greater decorum of their outward expression of such urges. When the Civil War began, violence came naturally to the left, who had long been primed for it and incited to it by their propaganda media and had actively practiced it in Asturias, Barcelona, Madrid and elsewhere. The same might be said of the Falangists, who had lost about sixty of their number as fatalities to left- ist violence before the war began and had slain an approximately equal number of their enemies.

From the start, both sides blamed the other for having initiated political executions and reprisals, and each claimed that the repression was much more widespread and vicious in the opposing zone."

"A common distinction between the Red and White terrors in Spain that has sometimes been made by partisans of the left is that the former was disorganized and spontaneous, and largely suppressed after about six months, while the latter was centralized and systematic, continuing throughout the war and long afterward. This distinction is at best only partially accurate. In the early months the Nationalist repression was not at all centrally organized, whereas that in the Popular Front zone had more planning and organization than it is given credit for. This is indicated by the many executions in areas where social conflict was not particularly intense, and by the fact that many of the killings were done by revolutionary militia coming in from other districts. Nor did the political executions in the Republican zone end after the close of 1936, though they did diminish in volume.‘

On July 28, 1936, the Burgos Junta declared total martial law through- out Nationalist Spain.® In Valladolid a consejo de guerra was set up within twenty-four hours of the rebel takeover. Further Junta rulings on August 31 and September 8 directed all Army and Navy courts to conduct proceedings as swiftly as possible and to suspend jury trials even for civil cases.* It was considered necessary to take strong measures from the start to establish control of a chaotic situation, but Mola himself was surprised by the rebels’ ferocity. The memoir of his secretary reflects the attitude of the rebel command. For example, early in the conflict Mola had occasion to order that a truckload of captured militiamen be executed at the side of the road. When he changed his mind and rescinded the order, a staff coloel complained, “General, let us not have to repent afterwards for mildness!”” Mola was said to have remarked, “A year ago I would have trembled to sign a death sentence. Now I sign more than ten a day with an easy con- science.” * At Seville, Queipo de Llano was even more outspoken. In his nightly radio broadcasts he made direct references to the brutal reprisals being carried out, apparently in order to terrify leftist listeners into submission.?

Juridical and police power was not centralized in the Nationalist zone until more than eight months had passed. Local and regional military authorities thus held direct responsibility for police action and proved implacable in execution. Franco himself set an important precedent during, the first days of the revolt in Morocco when, shortly after arriving to assume command, he approved the execution of his own first cousin, Major Ricardo de la Puente Bahamonde, who had resisted the rebellion as commander of the Tetuan airfield.'” Almost all the high-ranking officers in the Nationalist zone who had refused to join the rising were shot during the first year of the Civil War.'! "

"Of the two terrors, the White terror of the Nationalists was probably the more effective, not because it killed more people but because it was more concerted.

Though the military authorities were responsible for the great majority of the death sentences, executions were usually carried out either by the Civil Guard or by Falangists and other civilian militia. The first official circular of the Falangist Junta de Mando under Hedilla on September 9, 1936, tried to eliminate spontaneous acts of repression on the part of Falangist militia, ordering them to strictly obey local military command, which in many localities directed Falangists whom to arrest or shoot. Hedilla soon protested to Mola over the killing of gente de alpargatas (ordinary workers) and such incidents as the strewing of the Irún highway (near the French border) with corpses. A subsequent circular in November attempted to reduce Falangist participation in the repression. In his Christmas Eve radio address, Hedilla limited the Falangists’ role to the purge of the leaders of the left and of “murderers,” saying that in many areas there were “rightists who are worse than the Reds” and charging Falangists to protect ordinary rank-and-file leftists who had committed no crime." Eventually, in January 1937, he endeavored unsuccessfully to withdraw Falangists from participation in the repression altogether.** The climate of passion and hatred was such that, given the ruthless ferocity of the repression, there were very few protests among the more conscientious or squeamish Nationalists, even on the part of the clergy. During the first weeks, executions even became public spectacles in some areas, and on September 25, 1936, the Valladolid newspaper El Norte de Castilla protested the attendance of children and girls at such scenes. Finally on November 15 the ardently pro-Nationalist bishop of Pamplona, Olaechea, preached a sermon “No More Bloodshed, ’ which asked only that no more irregular killings occur outside the formal juridical process (though in Nationalist Spain the latter simply meant summary court-martial). Even Nazi and Fascist visitors were sometimes appalled, and occasionally suggested that the high level of violence might be counterproductive.

After Franco took over the jefatura única in October 1936, some effort began to be made to centralize the repression and assert the new government's control over courts-martial and the entire juridical process "

"The extension of central authority also brought with it some lessening of the extreme rigor of the repression, for Franco had begun to recognize that the number of shootings carried out by local authorities was excessive and might even be counterproductive for the Nationalist cause.

The final incentive for national integration of the Nationalist system of courts-martial was provided by the aftermath of the Nationalist/Italian conquest of the Málaga district in February 1937. There the victorious Spanish Nationalists under Queipo de Llano extended the practices common to the Seville district during preceding months, featuring summary executions in newly occupied areas often without even the simulacrum of a court-martial. This appalled their Italian allies, who were sometimes reluctant to hand over Republican prisoners directly to the Nationalist forces for fear of what might be done to them. The defeat of Italian troops in the Guadalajara offensive only a month later further increased the concern of the Italian commanders, eager to avoid reprisals by Republicans against Italian soldiers held prisoner."

The atrocities in Málaga and Italian protests apparently moved Franco to further action. A regularized Nationalist court-martial system was established in the southern sectors for the first time, with five militarcourts set up in Málaga to channel the repression. On March 4 Franco informed the Italian ambassador that he had given firm orders against shooting Republican POWs in order to encourage more to desert, and said that death sentences by court-martial would be limited to leftist leaders and those personally guilty of crimes, and that even in those cases only slightly more than 50 percent of those condemned would actually be executed. At the end of the month Franco informed the Italian ambassador that he had commuted the death sentences of nineteen convicted Free- masons in Malaga and removed two military judges there whose verdicts had been unjustifiable.'*

The end of March 1937 thus seems to have been the date at which Franco imposed the requirement that all death sentences passed by military courts must be sent directly to the Asesoría Jurídica of Martínez Fuset at his headquarters for review before sentence was carried out. Fuset organized these verdicts for Franco sometimes on a daily basis, and from that point the Generalissimo is said to have personally reviewed capital sentences of all courts-martial for political crimes. According to one version,’® Franco initialed all the names on such lists either with an E for Enterado (standing for “Informed and approved’) or a C for Conmutado (“Commuted). When the condemned was indicated to have been guilty of heinous personal crimes such as rape or murder, Franco is said to have sometimes added the words garrote y prensa, indicating that he should be executed by vile garrotte (strangulation with a metal collar) and the action should be announced in the press, something that was not ordinarily done. It has been claimed that Franco was more inclined to leniency in the cases of anarchists than of Marxists or Freemasons, believing the former more honest and redeemable and not under the influence of international forces emanating from Moscow or foreign Masonic headquarters. Conversely, Franco was not above occasionally intervening personally to direct more rigorous prosecution and sentencing (at least in a few cases), as he himself reminisced in later years.” The Generalissimo would also entertain rare personal representations from visitors urging greater clemency, but such visitors were few and received scant attention.”"

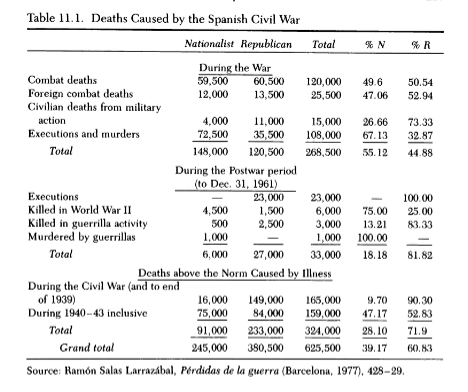

"Salas calculated that Nationalist executions during the Civil War amounted to 35,021, followed by 22,641 during the four years that followed (after which large-scale executions ceased), whereas those carried out in the Republican zone during the war amounted to 72,344. "

"Though Salas's work is by far the most systematic and probably comes near the truth in its global conclusions, it is nevertheless far from definitive. It is first of all not entirely clear that all executions were registered, even in subsequent years, though certainly the vast majority were. Beyond this lies the problem of complete and systematic investigation for every registry throughout Spain, beyond the task of a one-man investigation, and thus Salas has relied on certain totals and projections which are in some cases evidently incomplete. The figure for the number of Republican executions is perhaps too high by 10 percent or so, while that for Nationalist executions is probably an underestimation by an equal or greater order of magnitude. Such a conclusion is further indicated by the only detailed provincial study by Salas, dealing with Navarre. After examining 43 municipalities covering most of the province, he has raised the total of Nationalist executions there from 948 to approximately 1, 160%— an increase of more than 20 percent. Projecting the same proportionate adjustment nationally, this would produce an estimate of at least 42,000 executions by the Nationalists during the Civil War. Moreover, Salas subsequently raised his calculation of the number of postwar executions to approximately 28,000 to 30,000 for the entire period down to 1950. This would result in total Nationalist executions of 70,000 to 72,000 from beginning to end, almost exactly equal to the total in his computation of Republican executions during the Civil War."

"The general conclusion that there were less than 300,000 violent deaths from all causes during the Civil War years is almost undoubtedly correct, as is the one that the numbers of fatalities in the contending armies were approximately equal. Though the Nationalists were militarily more efficient, they were normally on the offensive, which ordinarily brings higher casualties, and thus these two factors tended to balance each other. On the other hand, the calculation by Ramón Salas of a distinctly higher number of excess deaths for the Republican zone also seems logical, for mortality from disease and malnutrition was considerably less in the better-fed, less-disrupted Nationalist territory. The rather low figures for civilian deaths caused by military action are also plausible. Though the Republicans initiated military attacks on civilian targets, their air raids of this sort were very few and quite weak. Franco and his allies limited themsleves for the most part to a certain number of raids on Ma- drid and Barcelona (as well as that on Guernica). Franco generally preferred to avoid destruction of civilian areas, and the noted “terror raids” on Barcelona in 1938 were carried out by comparatively small Italian units on direct orders from Mussolini and soon came to an end. Other civilian casualties sometimes resulted from artillery fire, but such victims were relatively limited in number."

"A decree of April 9, 1938, re- quired all persons of legal age, for the first time in Spanish history, to hold a personal identification card.”"

"Thus the close of the Civil War did not bring an end to the repression but instead facilitated its more efficient systematization. The wartime purges and courts-martial had rested on a most tortured juridical basis, applying the category “military rebellion” to those who technically had refused to support military rebellion, and refusing to apply the technical provisions of the Code of Military Justice that gave the rank-and-file of military units declared to be in revolt the right to submit without further penalty or prosecution.* Eventually a new juridical basis would be worked out for the repression, and as one major step in the new process of juridical legitimization, a special commission was appointed on December 21, 1938, to prepare an indictment of the legality of the Republican Popular Front regime of July 1936. This was composed of noted scholars and jurists, including several former cabinet members of the monarchy and the early Republican period. Its lengthy report, impugning Republi- can legitimacy, was published by the new Editora Nacional in mid-1939.™ This provided a theoretical justification for the conclusion of a postwar study of the crime of military rebellion which declared, “Defense of the old [Republican] political order constitutes the true rebellion.»

The end of the war did not bring to an end the militarization of the system of justice in Nationalist Spain. The state of martial law that had been declared by the Junta de Defensa Nacional on July 28, 1936, remained in effect and would not be repealed by Franco until April 7, 1948. Nominal political crimes would continue to be prosecuted by military courts, and both the Civil Guard and armed police would be commanded by Army officers and would be subject to military discipline. This situation, it should be pointed out, was not as unprecedented in Spain as in some other Western countries, for between 1934 and 1936 more than 2,000 civilians had been prosecuted by court-martial for their participation in the 1934 insurrection.

To establish standards for political prosecution, a special Law of Political Responsibilities promulgated on February 9, 1939, established penalties for political and politically related activities retroactive to October 1, 1934. The law had been drafted by the somewhat befuddled González Bueno, minister of syndical organization, with the aid of a small team of jurists. Its jurisdiction covered all forms of subversion and aid to the Republican war effort and even examples of “grave passivity” during the war.

Categories of persons automatically indicted by the law included all members of revolutionary and left-liberal political parties, though not auto- matically rank-and-file members of leftist trade unions, and anyone who had participated in a revolutionary People's Court in the Republican zone. Membership in a Masonic lodge was also automatic grounds for prosecution, despite the fact that the first head of the Nationalist Junta (Cabanellas) had been a Mason. Regional courts were established for each region of the country, with one central National Tribunal in Madrid. Three different categories of culpability were defined, with penalties ranging from fifteen years to six months.* For those convicted, the tendency was to impose heavy sentences at first and then reduce them later.

In addition to formal imprisonment, the law also provided for a variety of other penalties. These included partial or complete restrictions of personal and professional activities, and various categories of limitations of residence, ranging from expulsion from the country to internal exile, banishment to one of the African colonies, or house arrest. Wide-ranging economic sanctions were also included, which might extend from specific fines or levies to the confiscation of certain categories of goods or even total confiscation of personal estates.

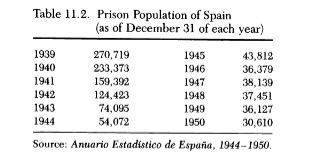

At the time of the final surrender, the prison population in Nationalist Spain was listed at 100,292,” though this figure does not include the huge camps set up to process the 400,000 or more Republican troops who sur- rendered in the last days of the war, as well as some 70,000 who voluntarily returned from France during the final month. During 1937-38 ordinary Republican troops taken prisoner had been freed almost immediately if no evidence of political initiative or affiliation was found, and a good many were rapidly redrafted into the Nationalist forces, which led to more than a few desertions. Most of the great mass of Republicans taken in 1939 were soon released, but nonetheless the incorporation by the Nationalist state of approximately one-third of Spain during the first three months of that year led to the greatest single wave of political arrests in the country's history.* At the close of 1939 the prison population stood at 270,719, though within a year or so that level began to drop rapidly"

"The best that can be said for the Nationalist repression is that it was not a Stalinist-Hitlerian type of liquidation and was not categorically applied by such automatic and involuntary criteria as race or class. It did tend, however, to be applied by general category to certain levels of responsibility in leftist and Republican political parties and trade union movements. Under such terms, cases were then dealt with on an individual basis according to the newly imposed legal criteria under military judicial process. As the most thorough scholarly investigator of this purge has put it, “The repression was constant, regular, and methodical. It was not arbitrary in character, even though it often seemed so. The repression was frightful, but it was also selective and rational.”"

"Once more, the most detailed study has been carried out by Ramón Salas Larrazabal; it concludes that the approximate number of political executions by the regime during the first six postwar years of 1939 to 1945 was 28,000.* After that point, direct execution became a rarity.

Franco did recognize some theoretical responsibility to heal the wounds of fratricide and bring the country together, but his method would be en- tirely his own and very slow to produce any such results. In a speech of December 31, 1939, he declared, “It is necessary to liquidate the hatred and passions left by our past war. But this liquidation must not be accomplished in the liberal manner, with enormous and disastrous amnesties, which are a deception rather than a gesture of forgiveness. It must be Christian, achieved by means of redemption through work accompanied by repentance and penitence.” Franco and his associates are said to have been particularly influenced by the prewar penal studies of a Jesuit, Julián Pereda, which emphasized that the goal of penal correction was rehabilitation and that the opportunity to work rather than merely be con- fined was an important aspect of this. Work would enable criminals in some sense to make restitution for their crimes, but should also be recognized and rewarded with modest wages.*

A decree of June 9, 1939, therefore established provisions for reducing sentences by up to one-third in return for volunteering for labor projects, and on September 8 arrangements began to create several “militarized penitentiary colonies” to assist in reconstruction.“*"

"Penal labor was involved in many projects during the immediate postwar period, especially in Morocco and Andalusia. The most important, however, was the special war memorial called the Valley of the Fallen, later to house Franco’s own tomb. Plans for this were announced April 1, 1940, the first anniversary of the end of the war.

The sort of rehabilitation that was attempted with political prisoners was not so much political as spiritual. During the first years after the Civil War the Catholic clergy played a prominent role in the penal system, holding obligatory religious services and attempting to catechize and convert many of those in jail. Nuns were particularly important in helping to administer prisons for women. For several years prison chaplains published a journal called Redención (Redemption), which published the confessions and stories of the conversion of convicted prisoners.

An active political opposition, along with very limited guerrilla activity, continued to exist. When a leading military police inspector was ambushed and killed on the Madrid-Lisbon highway on July 27, 1939, the response was swift and brutal: sixty-seven members of the underground United Socialist Youth (a joint Communist-Socialist organization) were rounded up and immediately tried, bringing rapid execution for at least sixty-three, including eleven young women, some of them under twenty- one years of age. The vindictive policies of the regime and the political encouragement provided the left by outbreak of general war in Europe combined to spark a further recrudescence of opposition activity by early 1940.

The Law of Political Responsibilities was thus supplemented on March 1, 1940, by a new Law for the Suppression of Masonry and Communism."

"Three years later, on March 2, 1943, Francos council of ministers approved yet another measure making any form of infringement of the laws on public order a matter of military rebellion. "

"Yet neither Franco nor most other top officials had any desire to run a system of concentration camps in Spain, and after a year had passed there was increasing concern to reduce the numbers of political prisoners. Franco took the first step on October 1, 1939, the third anniversary of his accession to power, when he pardoned all former members of the Republican armed forces who had been sentenced to terms of less than six years.This affected only a comparatively small number, however, and on January 24, 1940, a number of special military juridical commissions were created to review all sentences to date, with the power either to confirm or reduce but never to extend them. By the spring of 1940 there were still more than a quarter-million prisoners in Spanish jails. On May 8 the director general of prisons sent a special report to Franco pointing out that only 103,000 of them were serving confirmed sentences. The military court system proceeded rather slowly and in the year after the fighting had ended produced only 40,000 confirmed convictions. In addition to the latter group, another 9,000 had received death sentences, but most of these were still subject to appeal or reconfirmation. The fact that so many prisoners were potentially on death row was leading to riots and other acts of indiscipline, and consequently the Generalissimo was asked to do all that he could to speed up the juridical process before conditions in the overcrowded jails became unmanageable. Franco responded by increasing the number of tribunals and juridical personnel, incorporating more junior officials from the Military Juridical Corps.*

On June 4, 1940, the limited amnesty of the preceding fall was extended by granting provisional liberty to all political prisoners serving sentences of less than six years. From that time on, the prison population began to drop. Forty thousand political prisoners were freed on April 1, 1941, second anniversary of the end of the war, when the same terms were granted to all serving sentences of up to twelve years. This was extended to fourteen-year terms on October 16, freeing at least 20,000 more. During the winter of 1941-42 more than 50,000 more were released. An equally large group was amnestied on December 17, 1943, when provisional liberty was granted those with sentences of up to twenty years. During this same period, down to December 1943, approximately half of the 50,000 death sentences passed had been commuted to lesser terms.”"

"In March 1944 the minister of justice Eduardo Aunós is said to have informed a British journalist that about 400,000 had passed through the regime's prisons since 1936,” but the number still being held continued to drop sharply, sinking to less than 55,000 by the close of 1944 and to a nominal 43,812 a year later, of whom approximately 17,000 would be classified as political prisoners. Compared with the numbers imprisoned by many Communist regimes or by Nazi Germany, this figure was quite small, amounting to less than one-tenth of one percent of the general population.

Though repression remained firm and rigorous, it had largely ceased to be murderous. Even the large round of postwar executions had not assumed the capricious and sometimes genocidal forms found in the worst dictatorships, so that no analogy for those years can be drawn with Stalinist Russia, Nazi Germany, the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia, or even the arbitrary, capricious, and massive “disappearances in Latin American countries during the 1970s and 1980s. "

"Though it claimed tens of thousands of lives, the Nationalist repression recognized limits and normally respected its own rules. It also grew progressively milder with each passing year."