Chapter 1: The Politics of Modern Spain

17th-18th century

"During the seventeenth century Spain fell into a typically southern andeastern European pattern of ruralism, archaism, and slow economic development."

"Early introduction of modern parliamentary and constitutional liberalism (1810) gave Spain one of the longest modern political histories of any country in the world, exceeded among larger states only by Great Britain, the United States, and France. Early nineteenth century Spain was clearly not, by any normal set of criteria, properly prepared for modern liberalism, yet its precocious development seemed possible to the small minority of early Spanish liberals."

"One reason for this was the very long, if uneven, history of parliamentary institutions in Spain, for the initial late twelfth-century Cortes of León may have been the earliest of all medieval parliaments, antedating the Magna Carta. Another was the long and deep tradition of fueros (group rights and privileges), individual law and inheritance, and recognized autonomies within the peninsula."

"These factors help to account for the early emergence of minority, upper-class liberalism in Spain, but were far from sufficient to guarantee success for the nineteenth-century liberal polity. Popular illiteracy, extreme factional division, profound regional differences, and lagging, highly uneven economic development were only some of the major handi- caps it faced. Thus the record of Spanish liberalism from 1810 to 1936 was complex, halting, and to the casual student confusing in the extreme, sometimes seemingly more Latin American than European. Focusing on a myriad of discordant details can, however, easily obscure the overall pat- tern as well as the primary factors at work.

If one looks at modern politics in broad historical perspective, Spain's experience in many respects turns out to be more typical than has often been assumed.

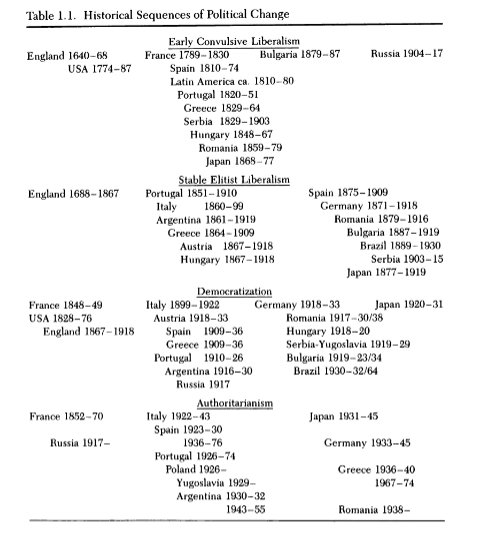

...The great majority of modern polities with a political history of a cen- tury or more have passed through a series of five major phases or se- quences between 1800 and 1950: (1) convulsive, unstable early liberalism: (2) stable, elitist, minoritarian (censitary) liberalism; (3) democratization involving new political and social conflict, normally leading to breakdown: (4) an authoritarian phase or interlude (sometimes occurring in two dis- tinct phases); followed in most west European continental countries by (5) a period of stable, institutionalized liberal democracy leading to systems of social democracy.

The stage of convulsive liberalism in Spain was long, from 1810 to 1874, compounded by riots, military revolt, civil war, and severe regional dis- cord. Only the fraternal Hispanic countries of Latin America went through such a lengthy period of convulsion. Part of the reason for this—and in- deed the principal distinction of Spanish liberalism—lay in the extreme precocity of Hispanic liberalism compared with its social and economic bases. The nineteenth-century Spanish political intelligentsia and elites persistently pushed through sweeping constitutional reforms, for brief periods giving Spain the most democratic suffrages and the most liberal political structures in continental Europe (in four distinct cycles: 1820— 23, 1836-43, 1854-56, 1868-74). No other polity attempted such ad- vanced political structures on the basis of such limited education, so little civic training, such an unproductive economy, such poor communica- tions, such extreme regional dissociation, and so much institutionalized opposition in sectors of the Church and Carlism. Stability was eventually achieved by a more modest, restricted form of liberalism in the oligarchic system of the restored monarchy of 1874.

In most modern states the initial period of convulsion similarly issued into a phase of relative stability based on elitist, oligarchic suffrage and leadership. In the case of Spain, universal male suffrage was reintroduced in 1890, but its effects were at first spurious if for no other reasons than the illiteracy, lack of civic interest, and poor communications among the lower classes. The existing patronage and party-boss system, commonly known as caciquismo, largely contained or deflected popular voting for about thirty years."

19th Century and weak nationalism

"The nineteenth century was a time of repeated civil war (1821-23, 1833-40, 1869-76) as well as of fre- quent military revolt and political insurrection. In addition, there were major costly colonial wars in 1810-25, 1868-78, 1895-98, and 1919-26, and many lesser campaigns in between. Spain, the great neutral, proba- bly spent more years during the entire period engaged in warfare of one serious kind or another than did any other European state. The effect of these in exhausting the public treasury and restricting economic growth was considerable—one of the major negative influences of the nineteenth century—yet since the conflicts were basically between Spaniards, they failed even to produce a sense of national unity, much less Spanish nationalism."

"The relative absence or weakness of nationalism in Spain, otherwise quite remarkable in comparison with other European countries, is less mysterious in the light of Spanish history. Spain is an old state even though it has never been a fully unified and centralized country. The first and for a long time the largest of the great European empires, it was more secure in its international role than most other lands. After the empire declined, Spain remained uninvolved in great power rivalries and suffered no foreign threat. The country had scant external economic ambitions or interests and coveted no one else's territory."

"The first major disillusionment with the Spanish ideology set in before the middle of the seventeenth century, and by the eighteenth century much of the earlier mind-set had faded away. It was revived by neotraditionalist thinkers in the nineteenth century, and in fact neotraditionalist Carlism became the only vigorous form of Spanish nationalism in that pe- riod. The fact that Spanish identity and the earlier Spanish sense of mission had been so completely identified with Catholicism proved a considerable hindrance in an era of modernization and incipient secularization. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries any pronounced sense of Spanish nationalism tended to be confounded with reactionary Carlism and with clericalism, thus divorcing it from the mainstream of public affairs.

The possibility of a Spanish nationalism was further retarded by Spains peculiar structure of reverse regional roles in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for the regions that dominated governmentally were not those that led the way in economic and cultural modernization. The latter normally provided new foci of leadership and identity in other countries. In Spain the industrial and commercial leader was Barcelona, which also happened to be the center of a somewhat distinct culture that eventually became the focus of a centrifugal regionalist nationalism, with a crippling effect on the Spanish polity. The same was subsequently true of Bilbao and the Basque industrial zone. Rural Castile and Andalucia, by contrast, lacked the social structure, economic base, or new culture to foster a dynamic modern Spanish nationalism. Resistance to Catalanism, in turn, took the form not of positive Spanish nationalism but of a sterile and negative anti-Catalanism that further undermined the polity.'"

"In Spain, nineteenth-century liberalism was too weak to accom- plish the one or the other. Pre-modern Spain had been a monarchical con- federation of distinct constitutional kingdoms and had never formed a fully centralized system. It remained the home of four distinct languages (Castilian or Spanish, Catalan, Galician, and Basque or Euskera) whose cultures were in fact revived and expanded by nineteenth century roman- ticism. Modern economic and cultural change did not unify Spain but threatened more and more to break it apart. To recapitulate, the chief reasons for the absence of Spanish national-ism may be summarized as follows:

-

Spains situation of absolute independence since the eleventh century, in which it became the first truly world empire in history and for long ranked among the established powers

-

The nature of the traditional Spanish state, a sort of dynastic confederation of strongly pluralist character despite so-called Habsburg “absolutism ”

-

The peculiar and exclusive mutual identity of traditional Spanish culture and religion, which created a climate of national Catholicism that endured for centuries and ended only with the full secularization that occurred late in the twentieth century

-

Absence of foreign threat after the Napoleonic wars

-

The long domination of classic liberalism, lasting nearly a century, conditioning formal culture and discouraging new military ambitions or the development of a modern radical right

-

The unique reverse role of regional nationalism, which absorbed much new energy

-

Neutrality in World War I

-

All this influenced and conditioned by, and to some extent even predicated upon, a slow pace of modernization, further accompanied by the absence of new political, economic, or cultural ambitions that might have stimulated nationalism

Regeneration

The political expression of regional nationalism received its first major stimulus from the Spanish disaster of 1898, which destroyed the remnants of the old empire and seemed to symbolize the failure of modern Spain as a state and system as well. The disaster also sparked a diffuse reform movement known as Regenerationism. In ideas, this produced a genre sometimes known as “disaster literature” (some of which had appeared before 1898) that suggested a variety of prescriptions and reforms for Spain's ills in a manner reminiscent of seventeenth-century arbitristas.

One strain of Regenerationism marked a new departure, introducing for the first time the notion of some sort of nonreactionary (non-Carlist or traditionalist) modernizing alternative to liberal and left revolutionary norms. Since the defeat of Bravo Murillos restrictive constitutional elitism in 1852, Spanish politics had been totally preoccupied with clashing doctrines of liberal parliamentarianism and leftist democracy, opposed by the counterplay of reactionary Carlist monarchism, increasingly feeble after 1876. Some contributions to the disaster literature took a different approach, rejecting traditional monarchism but leveling their main blasts against corrupt parliamentarianism, which was accused of distorting Span- ish life and making almost impossible the education, reform, and development of the country. A transition period of some sort of authoritarianism was occasionally suggested as a vague alternative."

"Reformism increasingly gave way to paralysis in the Spanish parliamen- tary system, yet the established middle-class Liberal and Conservative parties remained in place, however fragmented and ineffective. Unable to adjust to an age of democratization and mass mobilization, they nonetheless retained firm control of the electoral mechanism and levers of power, and after 1918 the Spanish electorate responded with growing abstentionism.

The breakdown of the parliamentary system that finally came five years later had no single cause. As in Italy in 1922, economic conditions were not a direct factor, since by that time the postwar slump had been largely overcome. The immediate causes were all in one way or another political. A mass working class left finally emerged after 1917 in Catalonia and a few industrial centers, employing tactics of violence and even terrorism. Yet the principal revolutionary force was anarchosyndicalism (the CNT), which could never be a major threat to the system because of the very anarchism of its organization and tactics. Regional nationalism grew stronger at the end of World War I, but the main Catalanist middle-class party (the Lliga) was soon forced to trim its sails drastically in the face of the internal class struggle in Catalonia. To an even greater extent, Basque nationalism lost its main voter support to a conservative reaction in the Basque provinces. ’

The breakdown was caused by the general loss of confidence in parliamentary liberalism, combined with the nasty stalemate of colonial war in Morocco. The failure of the dominant parties to function with unity and efficiency, to provide access and participation, and to solve problems eroded at least temporarily their support even among the middle classes, from whom their only broad support had ever come."

The Pretorian Tradition

"Since the inception of modern politics, the most common means of institutional or normative breakthrough in Spanish affairs had been military intervention.

...nineteenth-century liberals frequently confessed their reliance on the military. During that period, no change of regime (as distinct from government) in either a more radical or more conservative direction was made without either strong pressure or outright revolt by important elements of the Army. This variously took the form of intrigue or manipulation, the cuartelazo (a kind of barracks revolt or sit-down strike), a direct attempt at coup d'etat, or the more typically Spanish pronunciamiento (a term originating in 1820). The latter, as the word indicates, was a’ pronouncement’ that might take the initial form of pressure, manipulation, or outright insurrection. It was not necessarily aimed at immediate military occupation or overthrow of the government per se, but simply at rallying broader military or political support to effect changes in personnel, policies, or in extreme cases, the regime itself."

"In the process, the Spanish military developed a special role and identity that gave it partial institutional autonomy, yet most of the time the officer corps was itself almost as divided as political society in general...Most officers never participated in overt pretorian activity but simply followed orders, from whatever source."

"Before 1923, military dictatorship was never at issue. Pretorian rebels worked within the institutional framework of the liberal system and never sought to replace the regular structure of government with a military di- rectory. Politicized officers identified with standard civilian parties and doctrines, serving as the military wing of a broader political formation. Whenever a general ruled, it was at least nominally as constitutional prime minister and as the leader of a primarily civilian political party."

"The prevailing political sympathies of the military can be divided into several general phases. During phase 1 (1820-74), the primary tendency of military intervention was liberal, even though almost every liberal initiative was contested (and sometimes nullified) by a conservative one. Phase 2 (1874-1936) can be most easily described as centrist, though with an increasing tendency toward conservative and even right-authoritarian positions. The predominant political tone of the military became fully rightist and authoritarian only in phase 3, beginning with the inception of the Civil War and the Franco regime in 1936."

"The military began to play a more overt, and corporate, political role during the new systemic stresses of the early twentieth century. The first major initiative was the Cu-cut incident of 1905, an officers’ riot that sacked a Catalanist journal which had satirized the military. This resulted in the Law of Responsibilities (1906), which placed cases of libel and slander against military institutions under the jurisdiction of military courts. Much more important were the effects of the political radicaliza- tion and economic distortions of World War I. In Spains protorevolution- ary year of 1917, the officer corps itself began to fragment for the first time since 1873. Middle- and junior-rank officers began to form “Juntas mili- tares” in peninsular garrisons, creating a sort of officers’ trade-union movement to protest low pay, favoritism, and political manipulation by the senior command. They also acted as an influential pressure group against the Madrid government, demanding reform and forcing the resignation of two different cabinets in 1917-18.

The other two main sources of political pressure against the regime, the reformist liberals from the periphery and the revolutionary working-class movements, both hoped for some degree of military support, or at least benevolence, during 1917. Yet this almost completely failed to materialize, and the Spanish breakthrough of 1917 fragmented and splintered before it began to mobilize significant support. The officers’ Juntas made it clear that they were seriously interested in little more than corporate and professional privileges, and opposed the political radicalism of both the liberal and the revolutionary left. During the last years of the consti- tutional regime, the Juntas were largely neutralized through a series of carrot-and-stick manipulations, leaving the military even more divided than before.”"

"Thus there was no clear or simple military alternative to the liberal regime in 1923...Only the decisive initiative of Miguel Primo de Rivera, captain general of Barcelona, created the pronunciamiento of September 13, 1923, that overthrew constitutional government altogether...Timing of the pronunciamiento was triggered by several key events: resignation of three ministers of the latest Liberal government on September 3 to protest renewal of Spanish military initiative in Morocco, the parade of left Catalanists in Barcelona on September 11 which dragged the Spanish flag on the ground without remonstrance from the authorities, and the scheduled report of a joint parliamentary committee on September 16 concerning political culpability in the 1921 disaster."

Chapter 2: An Authoritarian Alternative: The Primo de Rivera Dictatorship